Integrated Care Systems for Children

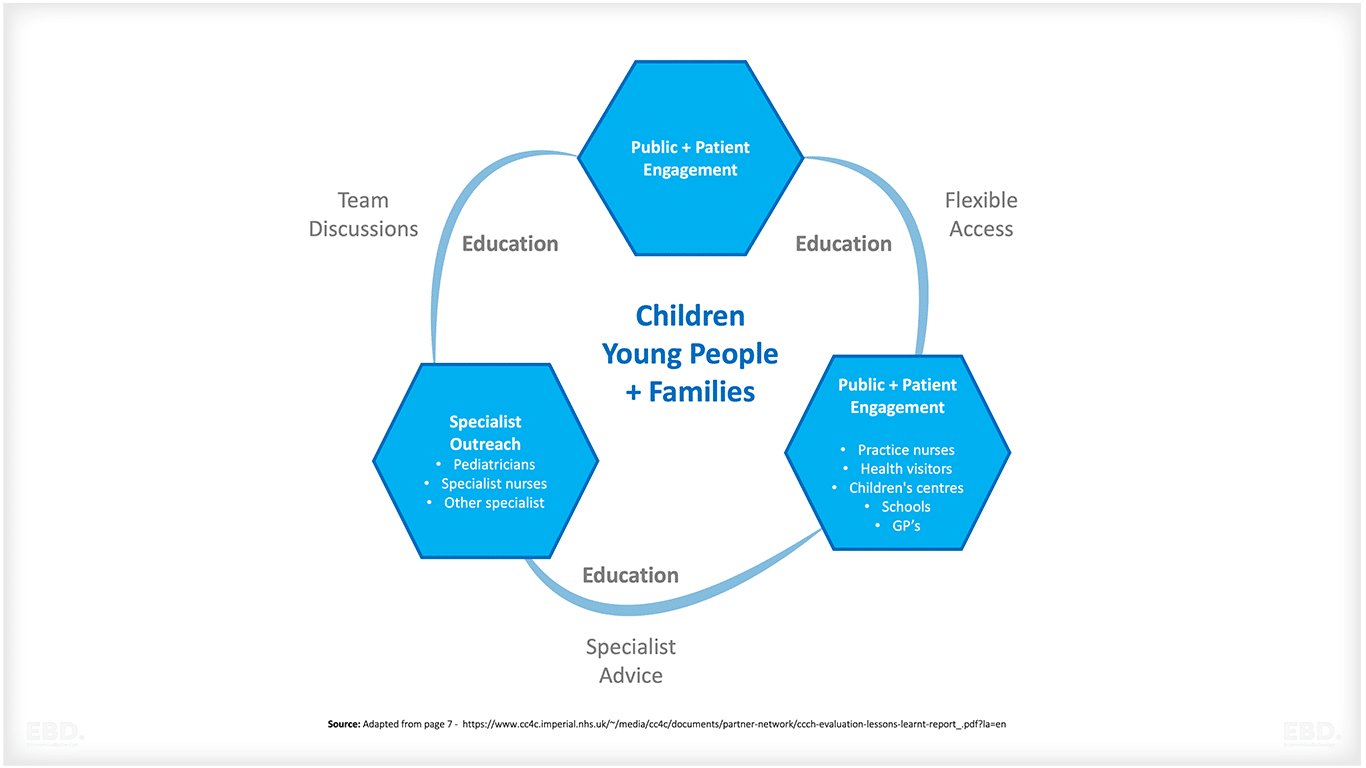

Integrated care systems for children can provide significant benefits for children and their families, for those working with children across the whole spectrum of health, social care, education and other services.

They enable the health care needs of children to be prioritised ensuring continuity and effectives of health interventions and the development of strong links with other partners in the wider communities where they live, go to school and socialise.

In this economics lens we take a look at the economic value of a well published example of integrated care system for children, namely the North-West London Child Health Hub , originating from the connecting children for care (CC4C) project.

The North West London Child Health Hub model provides comprehensive care for children with a range of needs, from pregnancy through childhood.

Their integrated services, including early years support, mental health services, and clinical care, have led to improved health outcomes and system benefits arising from the more efficient use of health services.

This successful model could inspire similar initiatives in other regions seeking better healthcare outcomes for their local population.

Child Health Hubs are for new and existing patients and can be used immediately to collaborate on patients with specific areas of concern e.g. readmissions, frequent A&E attenders, complex needs.

There are two parts to the model of delivery of a child health hub service:

1. Part A: Co-delivered care between general practice and consultant paediatrician:

-

- to ensure that specialist care can be delivered closer to home

- to build joint working between primary and secondary care services. Clinics are usually undertaken monthly.

2. Part B: Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) case discussions at GP hub;

-

- to bring together Children and Young People (CYP) specialisms (clinical and non-clinical) to discuss and agree solutions to patient cases.

- MDT case discussions will run monthly, and more frequently if agreed by partners

- each MDT will aim to discuss between nine and 12 cases

In 2022, Economics By Design (EbD) was appointed by North West London Integrated Care Board to undertake an economic analysis to support the development of a Business Case for the spread and adoption of the Child Health Hub model across all North West London Primary Care Networks.

A technical report was delivered which provided detailed analysis. Here we provide a synopsis of that analysis.

A summary of the benefits of integrated care systems for children

Studies have shown that integrated care systems for children offer the following benefits.

- Enhancing accessibility to local health services for children, young people, and their families.

- Streamlining care services through multidisciplinary teams in a single location, resulting in improved quality of care.

- Reducing waiting times and enhancing health outcomes by promoting efficient communication and collaboration between specialists and general practitioners.

- Promoting public engagement and education, enabling more informed decision-making.

- Increasing patient satisfaction through better coordination and communication with healthcare professionals.

- Realizing efficiency savings for the healthcare system by reducing hospital visits, emergency department attendances, and diagnostic tests.

- Developing improved care plans tailored to individual needs, fostering better communication between families and healthcare professionals.

- Optimizing the use of medical resources by minimizing redundant tests and integrating services across sectors.

- Expanding the capacity of general practitioners to provide local services through collaboration with paediatric consultants.

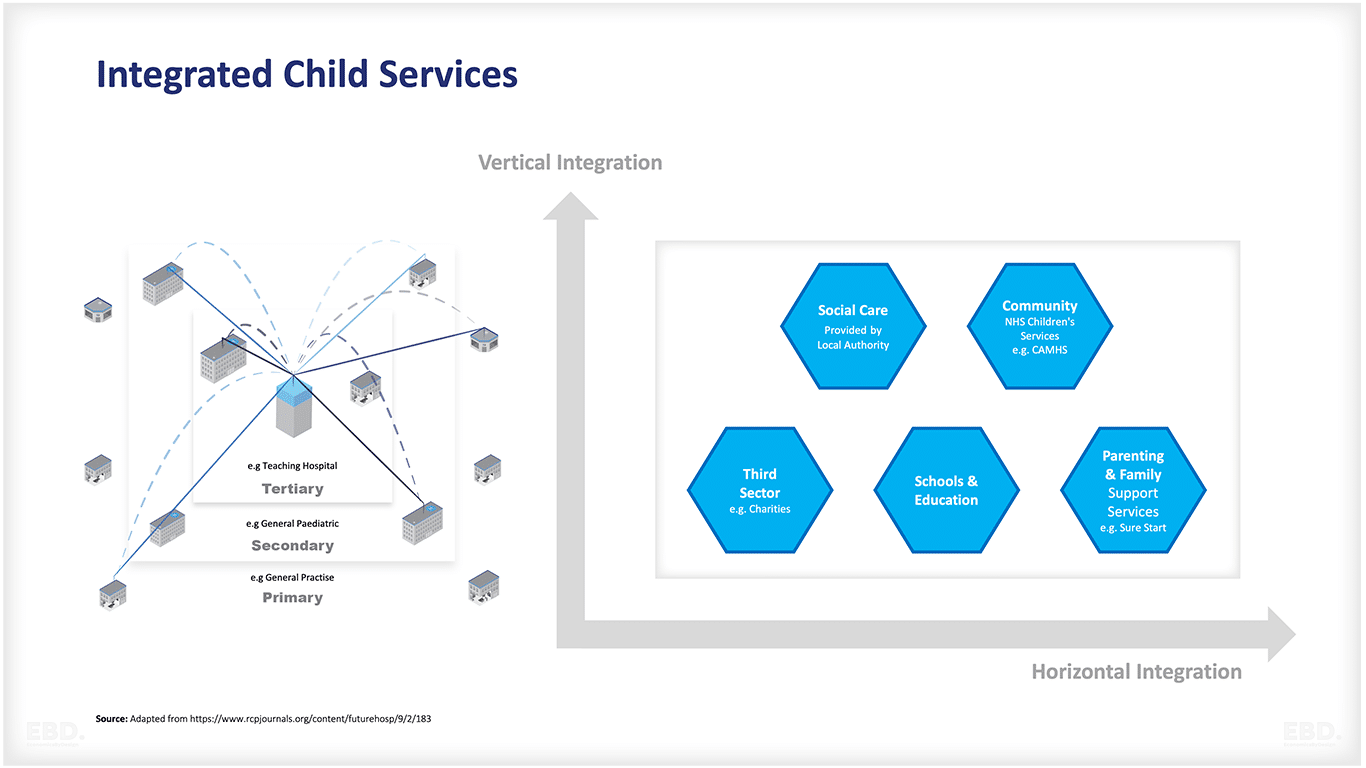

- Establishing stronger connections between primary, community, secondary, and tertiary health services to achieve a more unified approach to healthcare delivery.

The focus here is on the health system efficiency benefits of the Child Health Hub.

Development of the Child Health Hub

The GP Hub Model

The Child Health Hub, initially known as the GP Hub Model, was first established in 2012. Early pilots showcased the model’s potential value from a health system perspective.

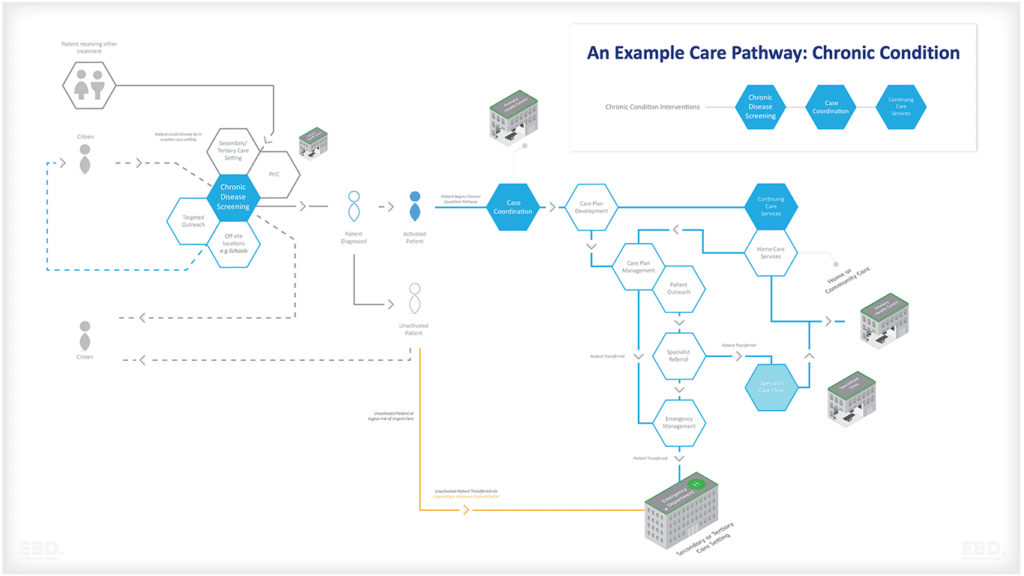

If proven effective, the model could redirect paediatric outpatient visits and, through a more integrated and efficient approach, prevent such visits, non-elective inpatient admissions, A&E attendances, and diagnostic tests.

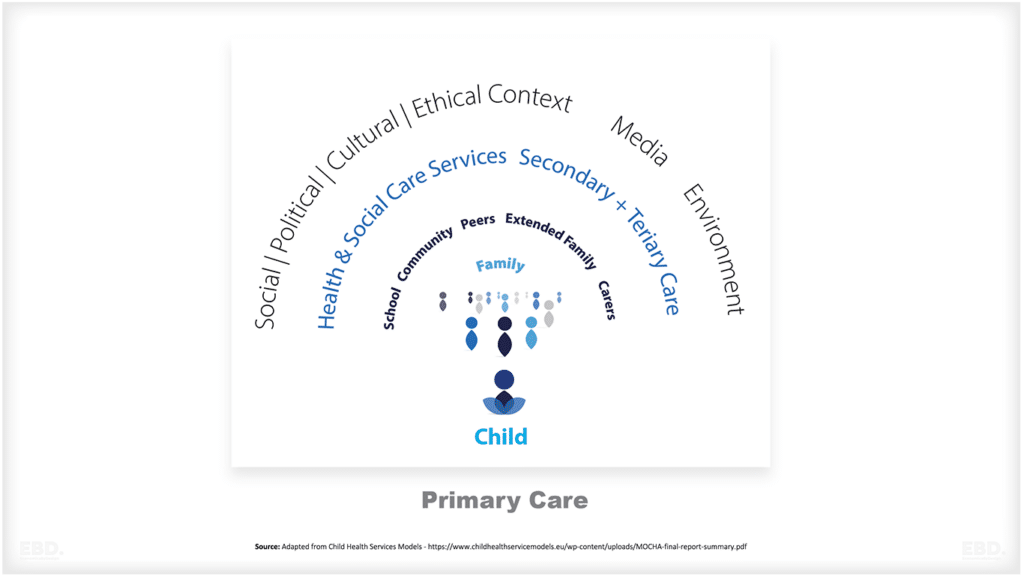

The original vision for the Child Health Hub was to facilitate seamless integration among primary, community, secondary, and tertiary healthcare services. Additionally, it aimed to establish strong connections with professionals in various sectors, such as education and social care.

A comprehensive approach, considering the entire lifespan of the population, was adopted to ensure effective service segmentation. The core principle of patient-centeredness was deeply ingrained, with a focus on fostering collaboration and co-production with children, parents, and caregivers.

Spread and Adoption

When the Child Health Hub was initially established, it operated within the framework of an NHS system that revolved around an internal market.

This internal market was built on the principles of choice and competition among providers, with complementary payment models and financial flows. However, for the Child Health Hub and many other integration initiatives, the benefits of system efficiency were not shared evenly across the various accountable partners.

The existing payment models also resulted in reduced funding for the acute sector, even though hospital-employed clinicians continued to support the service in a primary care setting.

These counterproductive incentives hindered effective collaboration across care settings within the health system. Additionally, the siloed design of the system necessitated special measures to pool budgets for multi-sectoral collaboration, which rarely targeted the needs of children.

Despite this, these integrated care systems developed organically and, by 2022, of the 45 Primary Care Networks, 17 were utilising Child Health Hubs across North West London.

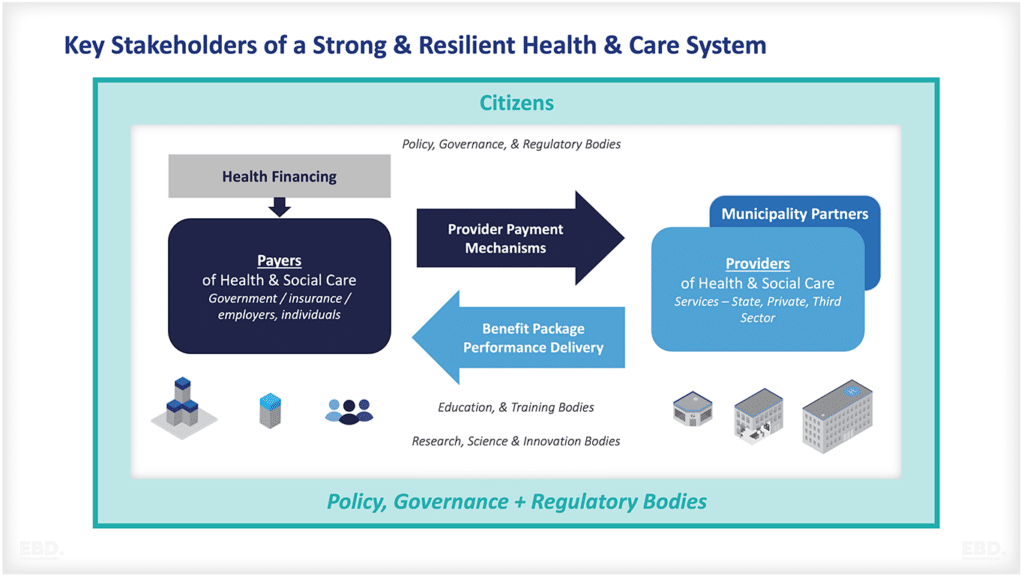

Since 2021, there has been a significant policy shift in the NHS in England towards a system design aligned with People Centred Integrated Health Services (IPCHS) advocated by the World Health Organisation.

This shift was initially outlined in the NHS Long Term Plan and implemented through the establishment of 42 Integrated Care Systems. The new NHS Health and Care Act 2022 enshrines the new integrated care system arrangements in law. Moving forward, there are ample opportunities to swiftly embed the new system design.

Model Development

Since its initial launch in 2012, there have been many other initiatives which influenced the current design of the model. These include:

- the potential development of Integrated Neighbourhood Teams,

- the focus on Core20Plus5 for children and young people,

- the development of Population Health Management (PHM), and

- the development of Family Hubs.

These have opened up opportunities to develop the Child Health Hub model to further focus on those children and families most at risk of poor health outcomes, and to engage with local authority colleagues and patient and public engagement initiatives more generally.

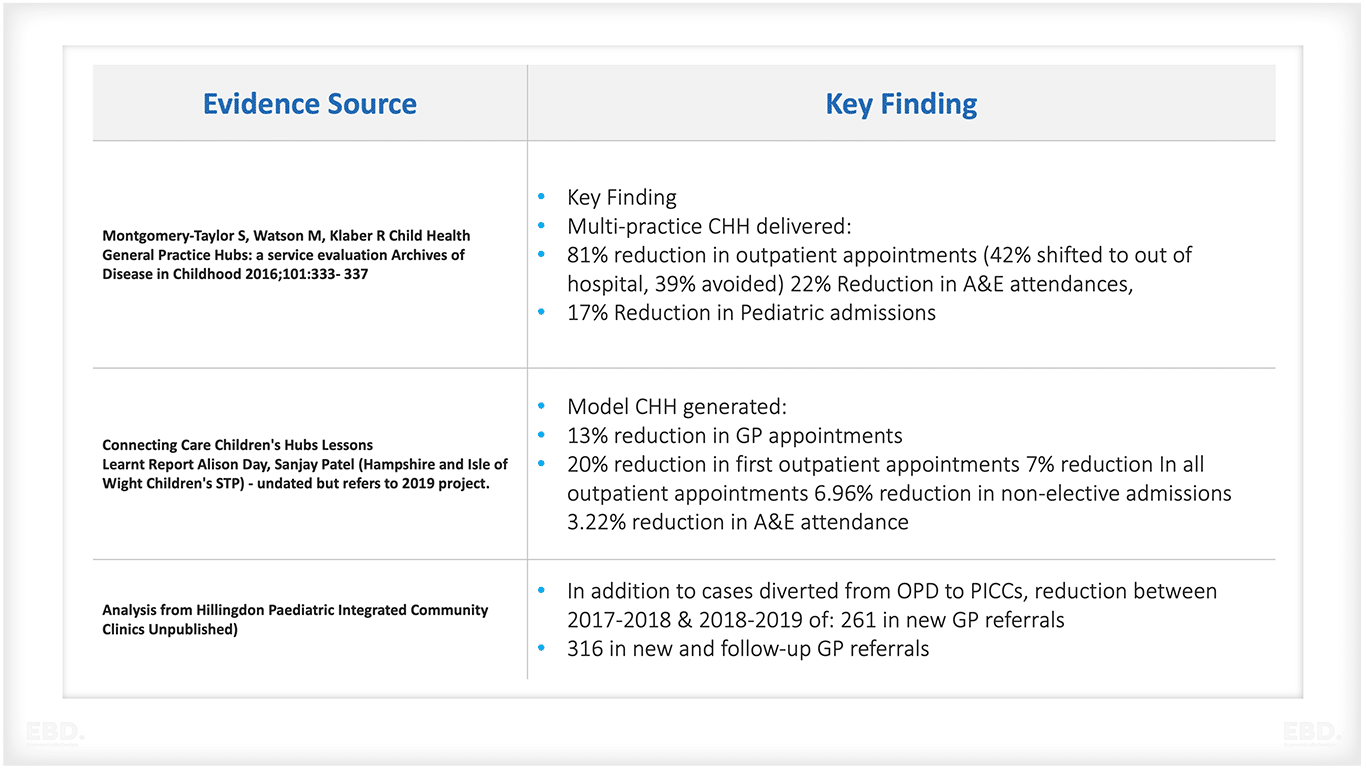

Evidence of Effectiveness

Gathering evidence to demonstrate the impact of service developments on health service efficiency is a complex and challenging task. Simple comparisons between practices with and without access to a Child Health Hub are confounded by numerous other factors that exist concurrently.

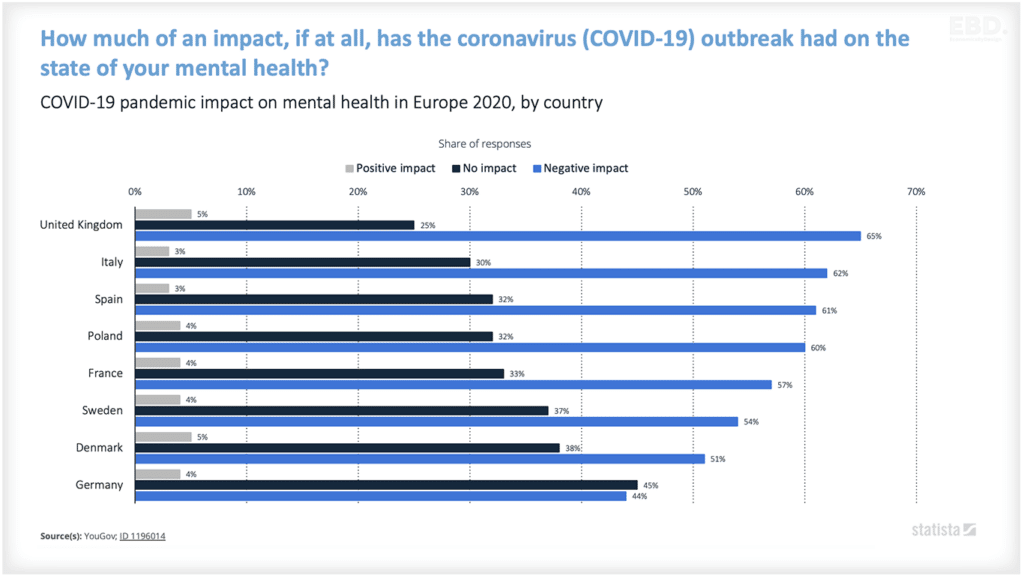

In recent years, services have been significantly disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a concerning increase in waiting times for primary care and hospital appointments.

Moreover, the issues are further exacerbated by the growing demands resulting from food and fuel poverty, which have been amplified by the economic pressures currently affecting the UK, and shortages of workforce across the health and care system.

However, there have been studies undertaken and the evidence regarding the efficiency of the health system is summarised in the table provided. The focus has been on the role of the Child Health Hub in preventing new hospital based outpatient attendances.

In addition, the model has been effective in reducing A&E attendances, hospital admissions, and GP appointments. Furthermore, there have been anecdotal reports of a decrease in inappropriate referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

It will be important to build evaluation into the further development of the Child Health Hubs to continue to demonstrate impact and value to patients, families, and the system.

Options included in the economic analysis

Four options were modelled in the economic analysis:

Status Quo

At the time the work was undertaken, there were 17 Child Health Hubs operating across North West London, and it was assumed under this option, these would continue in their current form to provide a baseline against which to compare the options for change.

The decline of the Child Health Hub

Failure to invest in the programme may lead to the withdrawal of existing Child Health Hubs and a return to traditional practices. The current model heavily relies on the dedication and passion of the staff leading them.

Without positive affirmation from commissioners, there would be a significant loss of enthusiasm and momentum. This option would result in the winding up of all 17 Child Health Hubs within the next 12 months.

Allowing the CHH to continue to grow organically

In 2021, nine Primary Care Networks (PCNs) expressed interest in the Child Health Hub, with the assumption that their integration would occur gradually over the next three years. However, this approach posed a significant risk of implementation failure.

Furthermore, it was anticipated that this would exacerbate existing inequalities by placing families and children registered with non-affiliated practices at a disadvantage.

Supported rollout of Child Health Hubs across North West London Integrated Care System

This would involve developing an enhanced CHH that consists of assigned Neighbourhood Team members (MDT), a funded coordinator (the existing coordinator roles did not receive additional funding), and funded Public Health Management (PHM) technical support.

The Child Health Hub would include participants from the Family Hub. To facilitate a smooth transition, new Childe Health Hubs would receive backfill for consultant and GP time to cover a 6-month period. The goal would be to establish Child Health Hubs in every Primary Care Network (PCN) within 3 years.

Accelerated supported rollout of the Child Health Hubs across North West London Integrated Care System

Under this option, the rollout would be accelerated and all 45 Child Health Hubs would be established within one year.

Summary of the economic model

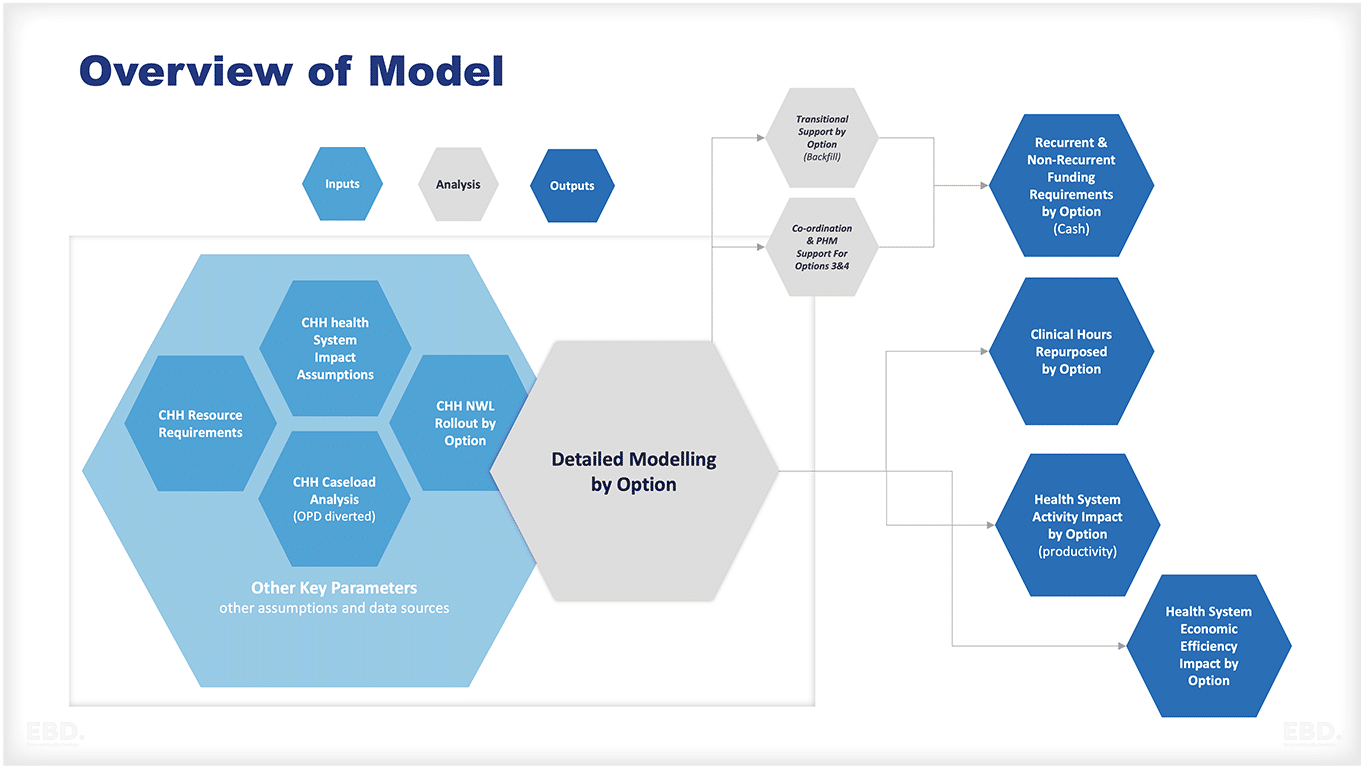

A straightforward economic model was developed to assess the potential impact of implementing each of these options on key metrics of health system efficiency. Additionally, the resources needed to fund the development of the supported rollout options were estimated and included.

The model took into account:

- the net additional resource requirements of the Child Health Hub and related support (under the supported roll-out options)

- the impact on outpatients (the redeployment of cases from acute to the Child Health Hub clinic and MDT) and the indirect impact of capacity released (some cases still need to go to the acute even having been seen at the CHH) and productivity differentials between the Child Health Hub and the standard outpatient department

- the wider health system impact including outpatients referrals prevented (in addition to the cases seen at the Child Health Hub), A&E attendances prevented, admissions prevented, GP appointments prevented, and potentially CAMHS referrals prevented

- the number of Child Health Hubs over time under each option.

- the potential that the supported roll-out options would be more effective in terms of health system efficiency impact than other Child Health Hubs as they have assigned Neighbourhood Teams and PHM support

The analysis was undertaken at a 2022 price base and a 10-year perspective was used for all options. Unit cost information was taken from the PSSRU Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2021 (Jones, K. & Burns, A. (2021) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2021, Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury. DOI: 10.22024/UniKent/01.02.92342) and NHS November 2022 NHS Tariffs.

CHH Resources

For the purpose of the economic modelling, Child Health Hub resources were assumed to comprise for a PCN covering a total population of around 45000:

- A consultant paediatrician who would be available for 6 hours a month for clinic attendance (including travel and administration, a further 1 hour per month for the MDT meeting and on average 4 hours each month for direct access for questions and advice relating to the management of patients and families.

- A general practitioner who would be available for 4 hours per month to attend the clinic and a further 1 hour per month to attend the MDT (on-line).

- Additional MDT members comprising health visitors, community nurses, dieticians, mental health practitioners, school nurses, etc. On average 5 additional MDT members would attend the monthly one-hour MDT meeting. In addition, a further 2 local authority representatives would attend, under the supported roll-out options, these would be nominated by the Family Hub as these develop.

- The existing Child Health Hubs have coordinator support. This would continue at around 8 hours per month. Under the supported roll-out options, there would, in addition be 4 hours per month support from a PHM coordinator to enable focus on Core20Plus5.

Assumptions about health system impact

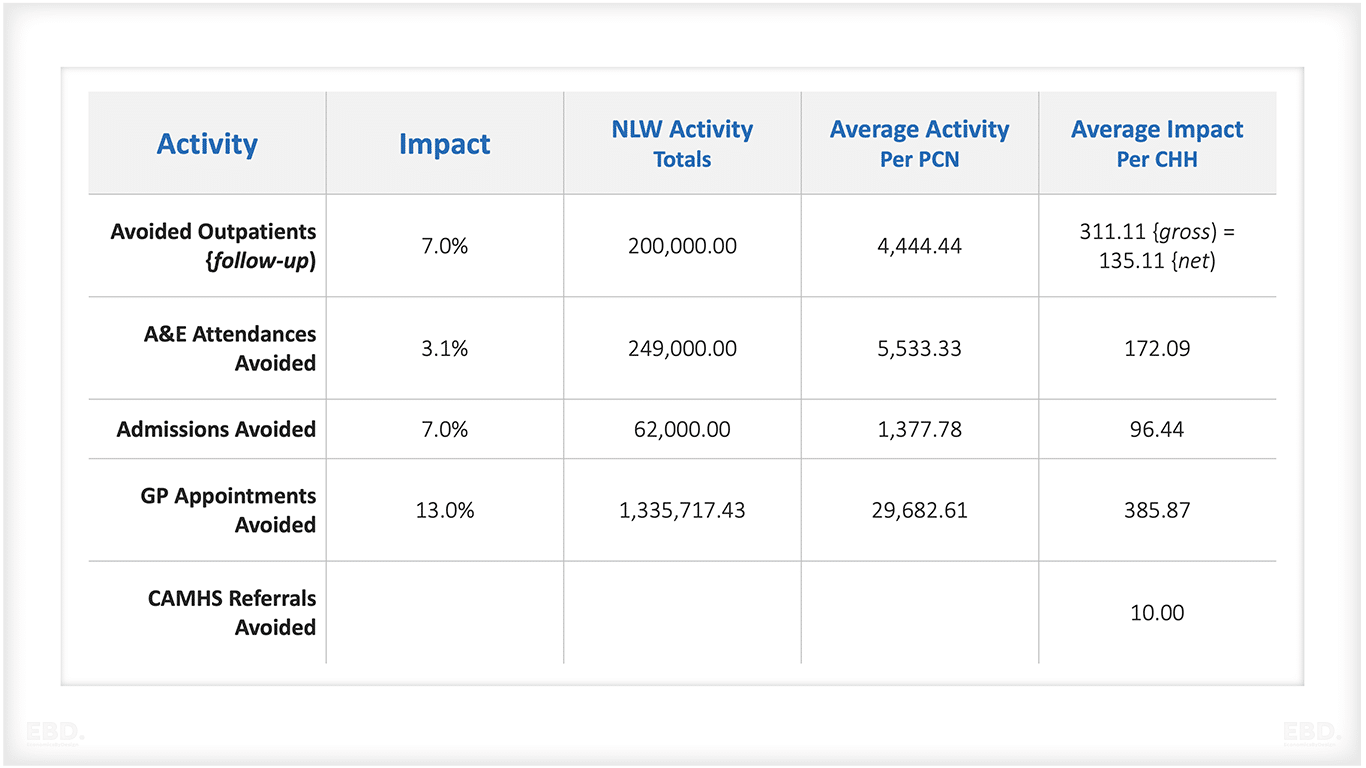

Conservative assumptions were developed with the local clinical teams and adopted for modelling the potential impact on health system efficiency (much lower than the evidence suggests). These were applied to the North West London activity data for 2021-22, and are summarised in the table below

The table above shows that, on average, around 176 outpatient attendances are diverted from hospital-based clinics to each Child Health Hub (311-135). However, in addition it is assumed that there will be a further reduction of 135 attendances per Hub as a result of the new service model.

Given that the Child Health Hub cases are new appointments, it has been assumed that the avoided outpatients are likely to be disproportionately repeat or follow-on attendances. This is a conservative assumption since follow-up attendances have shorter appointments and consume relatively less resources than new appointments.

For GP Appointments Avoided, the impact estimate of 13% was further deflated to 10% of its value (i.e. 1.3%). This is an arbitrary adjustment but reflects the absence of corroborating evidence of this impact from other sources.

For the CAMHS referrals, there is no evidence of impact other than anecdotal reports of a reduction in inappropriate referrals. For the business case therefore, a simple illustrative assumption was included of 10 cases avoided per annum per Child Health Hub.

To mitigate any optimism bias, it was assumed that for the current Child Health Hub model, only 50% of the impact would be achieved and for the model supported by a PHM approach, only 80% of the impact would be achieved.

Results from the economic model

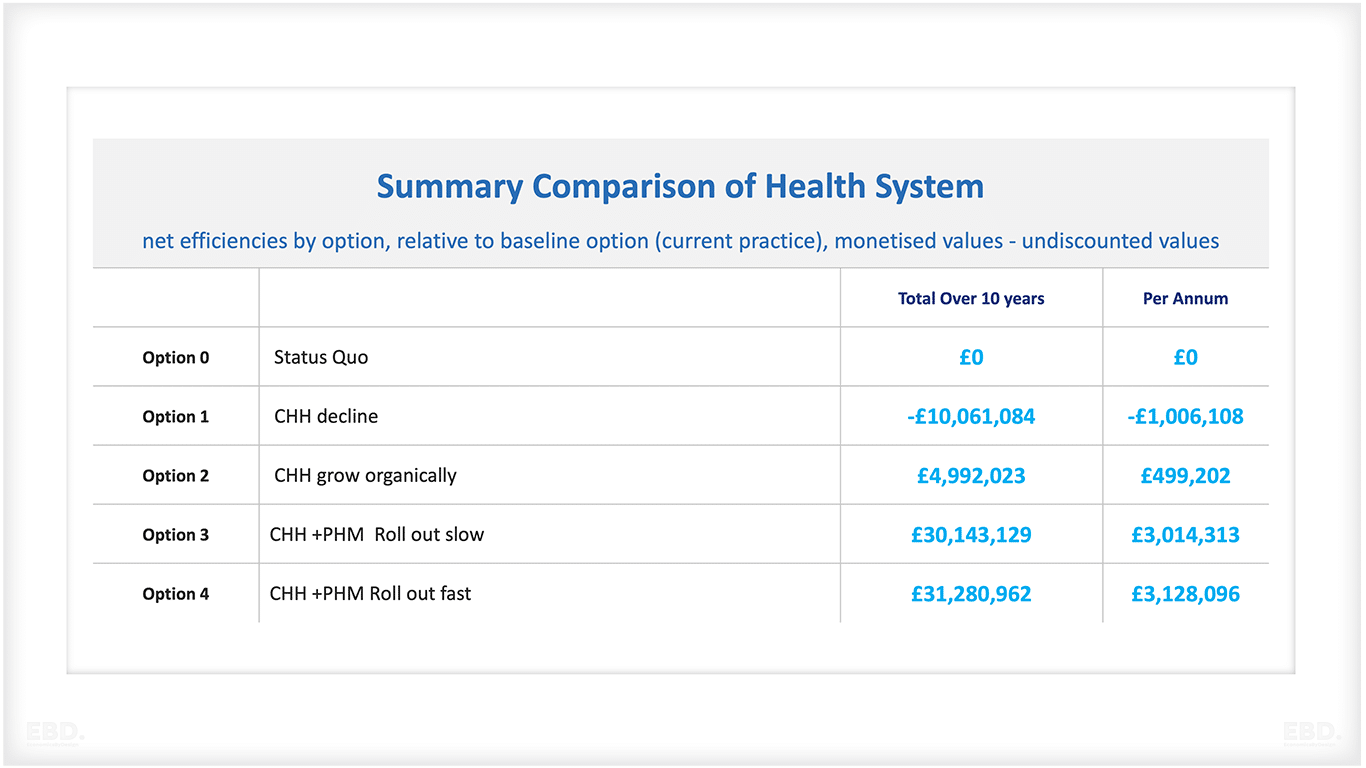

The estimated monetary value of the health system efficiencies generated by the Child Health Hub for each of the options is shown in the table below.

These estimates show that if the existing Child Health Hub are discontinued, there is a potential loss of net health system efficiencies for North West London over 10 years. Expressed in monetary values this equates to £10m, which, once discounted to reflect the economic value of efficiency now versus later, equates to £8.3m in present day values.

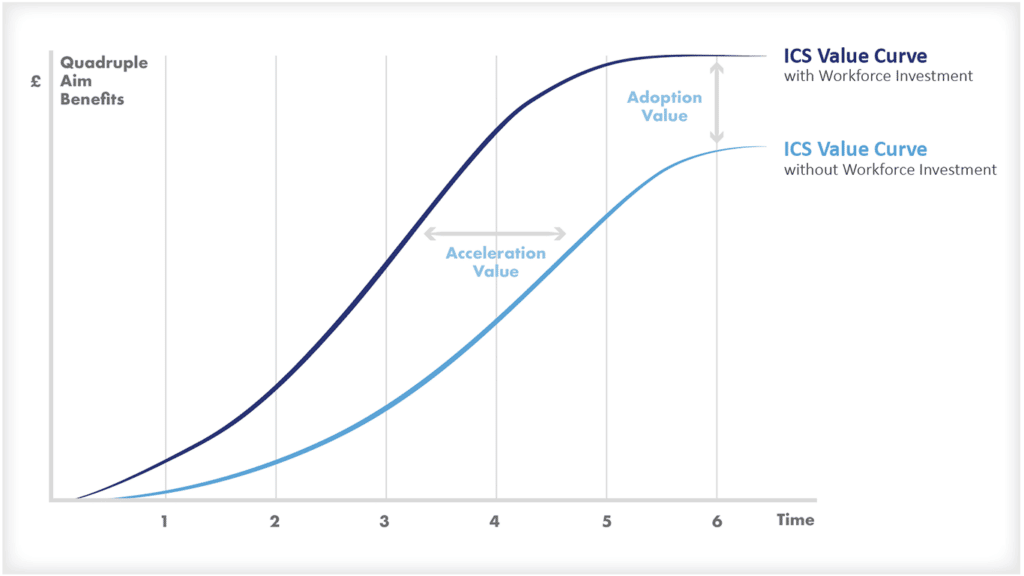

Continuing with the organic growth of the Child Health Hub, if feasible, would add net additional health system efficiencies with a monetary value of £5m, with a present-day value of £4m. Options 3 and 4 offer much greater health system efficiencies with Option 4 showing higher values given the accelerated implementation.

Option 3 shows a net efficiency valued in monetary terms of £30.1m (£24.6m present day value), and Option 4 a net efficiency value of £31.3m (£25.7m present day value). Option 4 is the preferred option overall in terms of health system efficiency. Sensitivity tests were undertaken and the preference ranking of the options was unaffected.

If the option to reduce the number of Child Health Hubs is chosen, it may lead to a significant increase in pressure on outpatient services. In addition to the cases that would be transferred back from the Child Health Hub, there would be a need for additional capacity to handle 114 new ongoing cases and a potential 1148 follow-up cases.

This would result in an annual increase of 1463 cases in A&E, 820 additional inpatient admissions, and a continued rise in pressure on GP practices with an estimated 3,280 extra appointments required. The evidence also indicates a likely increased strain on CAMHS. To cope with the efficiency loss, the system would require an additional 2 paediatricians and more GP time.

In the case of organic growth, the current model’s benefits persist and are further amplified by the inclusion of an additional nine Child Health Hubs. Nevertheless, when compared to Options 3 and 4 over a span of 10 years, the net benefits would be rather modest and result in unequal access within the North West London system.

The rollout options that are supported yield the most significant efficiencies when the Child Health Hub is fully adopted by 45 Primary Care Networks. Among the options, accelerated rollout offers slightly greater benefits over a 10-year period due to its earlier rollout, which allows for accelerated access to the benefits of the Child Health Hub.

The efficiencies generated by the supported rollout options are equivalent to the impact of appointing 5.2 new paediatricians in comparison to traditional practice, along with an additional 1.44 general practitioners.

Concluding comments

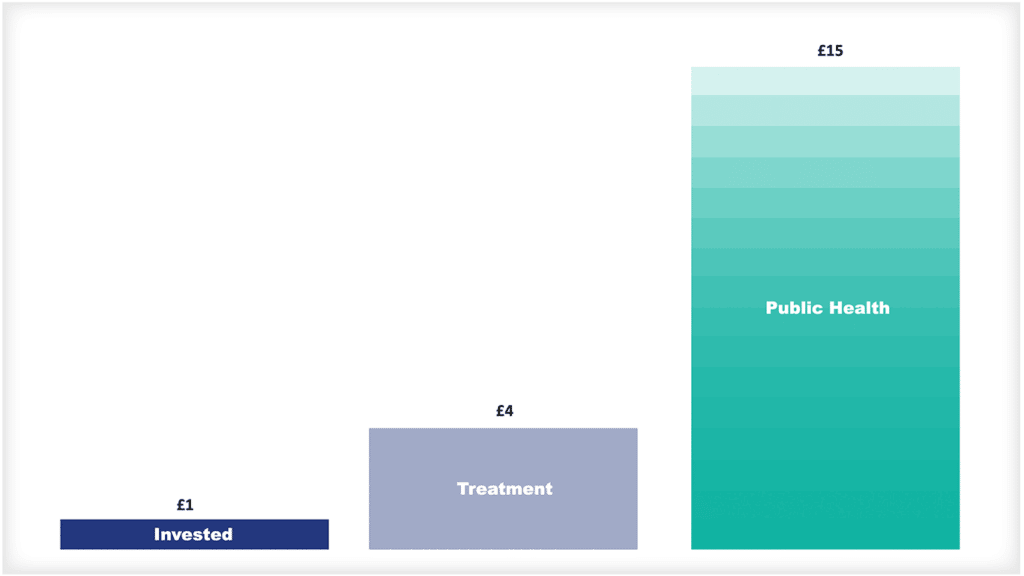

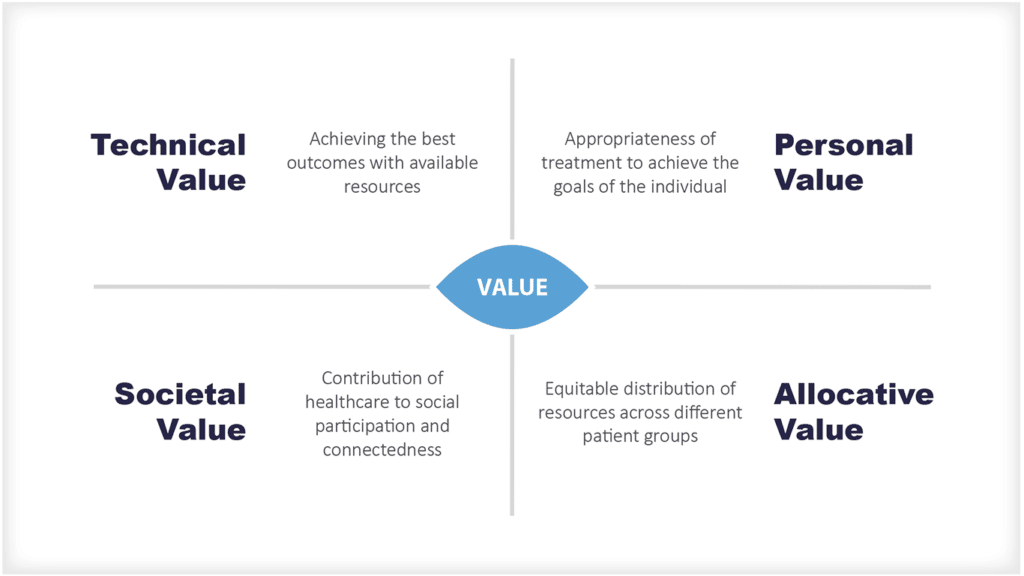

The economic analysis has demonstrated that significant efficiencies within the health system can be achieved through the widespread adoption of the Child Health Hub integrated care system in North West London. This model, supported by a Population Health Management (PHM) approach, has the potential to generate efficiencies that are equivalent to the impact of employing additional paediatricians and general practitioners.

These models are not intended to generate immediate cash savings, but rather provide a cost-effective framework for improving population health. Additionally, they help Integrated Care Systems manage the underlying growth in demand, system cost pressures, and staff shortages.

In 2023, NWL ICB took the decision to support the further roll out of Child Health Hubs. Transition funding has been provided, to enable the release of clinician time to establish this model of working across Primary Care Networks in North West London. In addition, funding for coordination and Population Health Management has been provided to new and existing Hubs.

The ICB Children and Young People’s Clinical Network has an active workstream which aims to further develop the Child Health Hub model, enabling a shift towards a proactive model of care to ensure that the needs of children and families can be met at the earliest point, and to build upon the efficiencies in health utilisation that are delivered as a result of this model.