Building Value Into Workforce Planning In the NHS

Pressures to cut costs are getting worse, yet it is more important than ever to reverse the trend of treating workforce as a cost and not an asset, when developing workforce plans and approaches.

Many organisations and systems that we work with see workforce as a cost. Requests to hire are scrutinised and blocked, vacancies are seen as a way of reducing overspends and capacity plans to recover backlogs are essentially just plans to “sweat the assets”.

More Integrated Care Boards and Organisations are entering various forms of “Special Measures” for financial reasons and the NHS is facing unprecedented levels of overspend – the Guardian is reporting in September ’23 that the NHS will be £7bn in debt by 2024.

In their plans and actions, health & care organisations generally balance the needs of three key things:

- Service-users or patients – the people that the service exists for

- Workforce – the people that deliver the service

- The organisation – the entity that brings the staff and the service users together to generate value

Our experience of working in cost reduction and health economics tells us that it is pressure that tilts the balance towards one group or another. At the moment, we are seeing pressure on all three of these areas.

- Service user demands are increasing in terms of just a sheer growth in activity – with hospitals we are working with facing consistent, future demand growth predictions greater than 5% per year.

- Existing workforce are under pressure as is evidenced by strike action and higher levels of staff turnover.

- The organisation is under-funded, under-capitalised and, as a result under-performing.

But it is the cost pressures that appear dominant at the moment – at national, regional, system and organisation level.

If pressure tilts towards cost, it generally leads to reactive, short-term responses to cut it. What is needed is long-term strategic workforce planning. But short-term pressures get in thje way. Organisations and systems act as if in private sector “turnaround”. As well as damaging the staff experience and damaging service-user outcomes, this is leading to the opposite of what it should intend – an increased cost to serve over the long term.

The Institute for Governance’s excellent “The NHS Productivity Puzzle”, highlights the need for this apparently counter-productive approach to reducing cost. Great investment in technology AND STAFF is needed if we are to truly create a cost-effective, high quality service.

Health systems and organisations need to continue to focus on the staff while they look to control cost and handle rising service-user demand. They must build in time for training, up-skilling and nurturing staff when developing workforce plans in a world of rising service-user demand levels and pressure on costs – and view staff as an asset by measuring their impact on the service, not their cost.

Workforce planning the old way, where value only equals cost

We’re old enough to remember back to the early 2000’s when the talk in health trusts was all about cost control and cost reduction. When trusts that were underperforming financially needed to develop a Cost Improvement Plan (CIP), a Performance and Efficiency Plan (P&E), Cost Reduction & Efficiency Scheme (CRES) or some other management consultant led strategy for operating within their means.

At the time, these would focus on the scope for reducing whole time equivalent posts on the basis that the workforce accounted for nearly half of healthcare costs. However, this looked at our workforce through completely the wrong lens. Instead of seeing the NHS workforce as a cost that needs to be controlled, we should be appreciating that health professionals are a valued asset to be nurtured.

Trusts looking at “cost” explored two choices to control it – either to pay less into staff bank accounts or to pay less into suppliers’ bank accounts. Again, that is, in itself, correct if you are just looking at these resources as a cost, as this sees workforce spending as undesirable and something to be reduced.

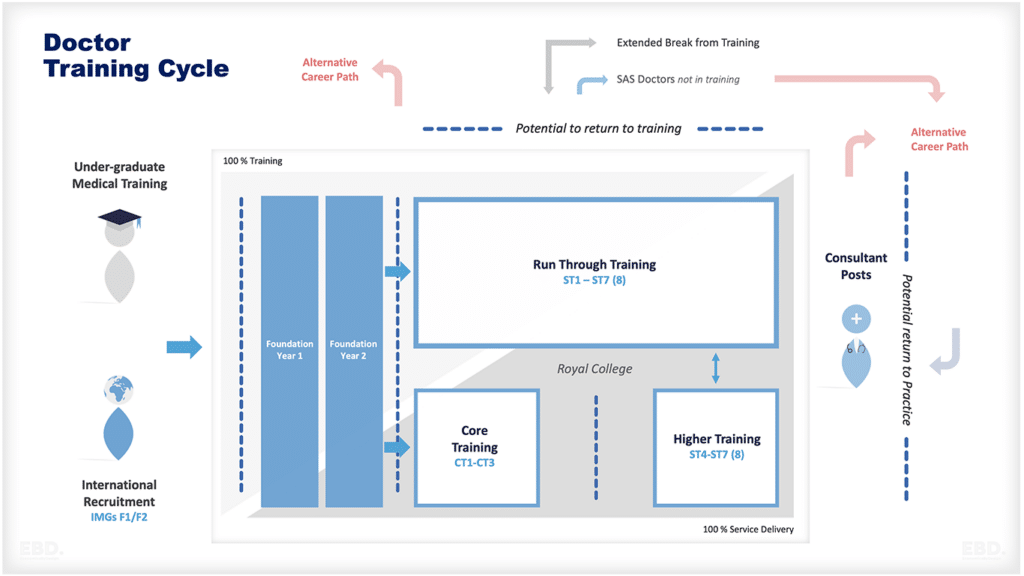

Fast forward to 2023, through the days where the waiting in A&E and eventually for elective care burst through the allowed maximums, through the folding of PCTs and the invention of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), through the years of COVID and the urgent suspension of contracts and payment models and emerge into a nascent world of Integrated Care systems, population health and more efficient care coordination.

Immediately post Covid-19 there was a lot more discussion about demand and inequality than there is about cost and more discussion about workforce morale, wellbeing, retention. Overall, the conversation was about the shortage of staff needed to meet demand, and for a few years, we were not talking about staff from the perspective of cost. Despite the fact that the government had seen fit to cut pay to NHS staff in real terms.

This year, that has changed. Pressure on costs is back, and back with a vengeance, like the bad old days of turnaround. Integrated Care Boards are being supported by NHS England to control their expenditure. Workforce growth plans are being challenged by NHS England when submitted Regional plans are highlighting efficiency as a priority when considering workforce. And finally, National costs are high, and in the news.

Turnover has dropped from the levels of The Great Resignation, but remains historically high. At the same time, those that bore the brunt of the pandemic have suffered significant moral injury (see previous article), are more likely to be ill and leave the profession faster.

Following the impact of COVID there is now greater underlying demand for healthcare, pent up demand in waiting lists and fewer people to deliver care. The balance between supply and demand isn’t just out of line – it has practically collapsed in a heap.

Despite the temptation, we must not revert back to the old way of workforce planning, where value only equals cost.

Workforce planning the new way, where value equals efficiency and effectiveness

Five Steps to Build Value Into NHS Workforce Planning

In our view, NHS organisations at all levels can only correct course by building value into workforce planning. They can do this by:

- Step 1: Building realistic workforce plans that show the gap between staff needed and staff we can afford – and having a robust conversation about bridging that gap at Executive level, rather than ignoring it and hoping it will address itself.

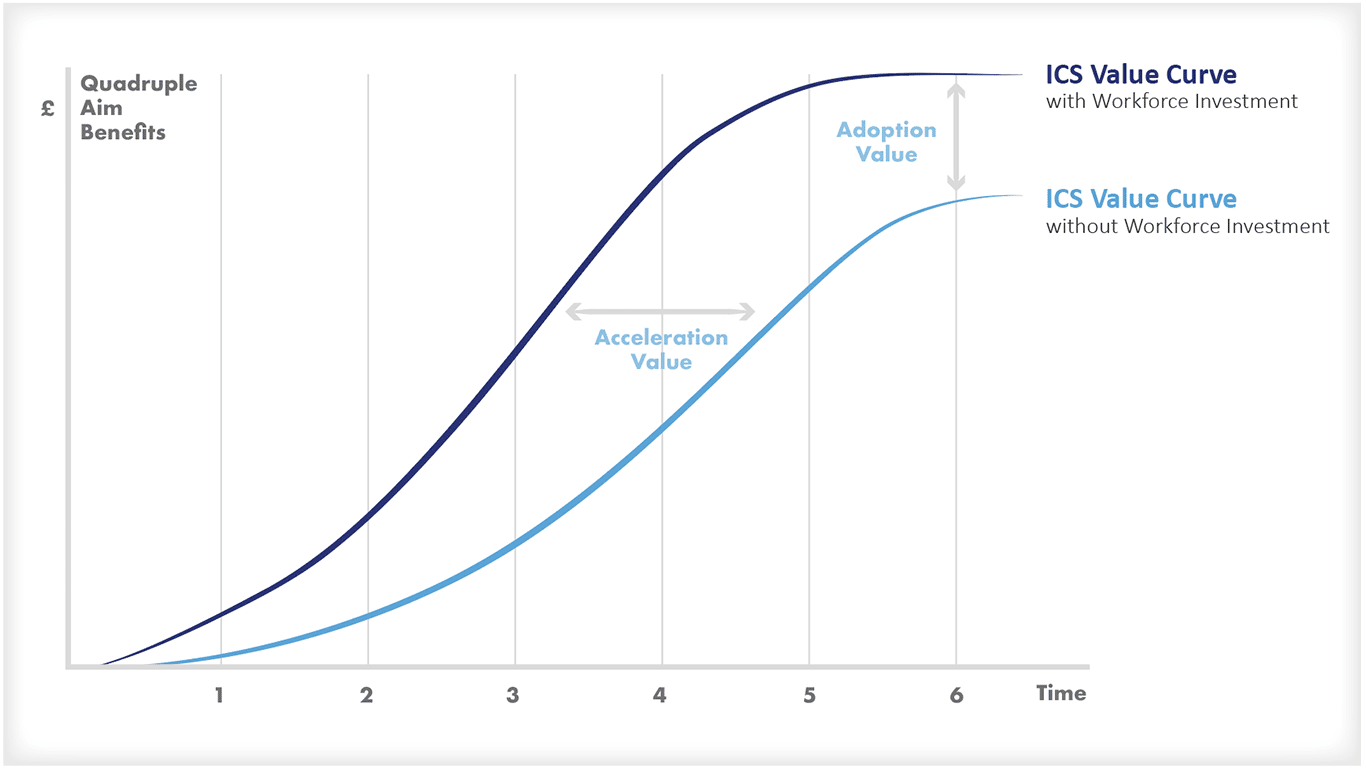

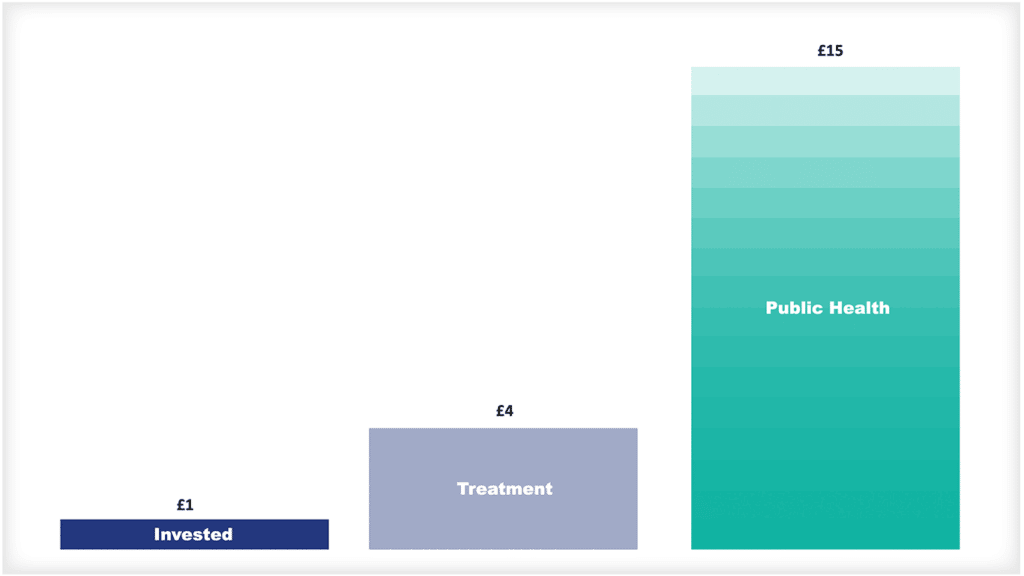

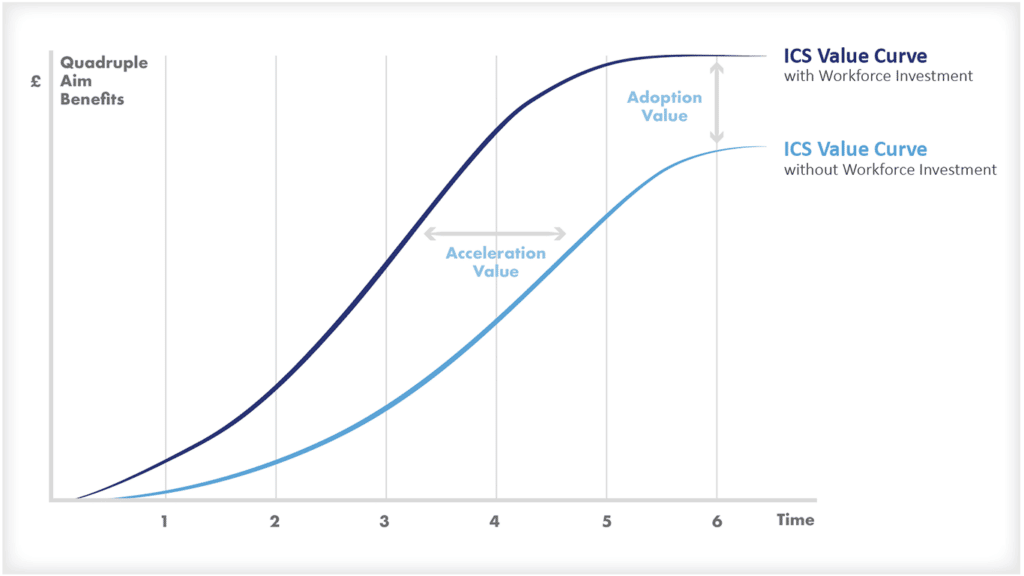

- Step 2: Demonstrating the economic value of the health workforce to ensure that finance teams can clearly see that short-term cuts lead to short and long term increases in costs

- Step 3: Investing in real, appreciative leadership from the front-line, down to central departments.

- Step 4: Dual Transformation: Empowering staff to innovate to solve problems while the big redesigns are happening – because only with this will the gap be bridged.

- Step 5: Defining the rules of working in an era of high activity, so that staff do not bear the brunt of decisions as to who will receive care.

Only through a planned approach to improve efficiency by focusing on staff, and showing their financial value to the organisation, will we be able to control cost and meet the needs of the organisations.

Step 1: Build proper workforce plans

In The Bumper Book of Health & Care Workforce Planning, Colin has detailed the basics of writing a good workforce plan. Alongside tips for actually making these proper plans rather than beautifully crafted but completely unusable spreadsheets, they include a process that anyone can follow. Key elements include:

- Clearly set the challenge for all organisations and individuals in the system, and align and monitor the delivery of activity against the main challenges

- Focus on delivering a small number of high impact changes centrally, one of which should be building world-class leadership and management skills

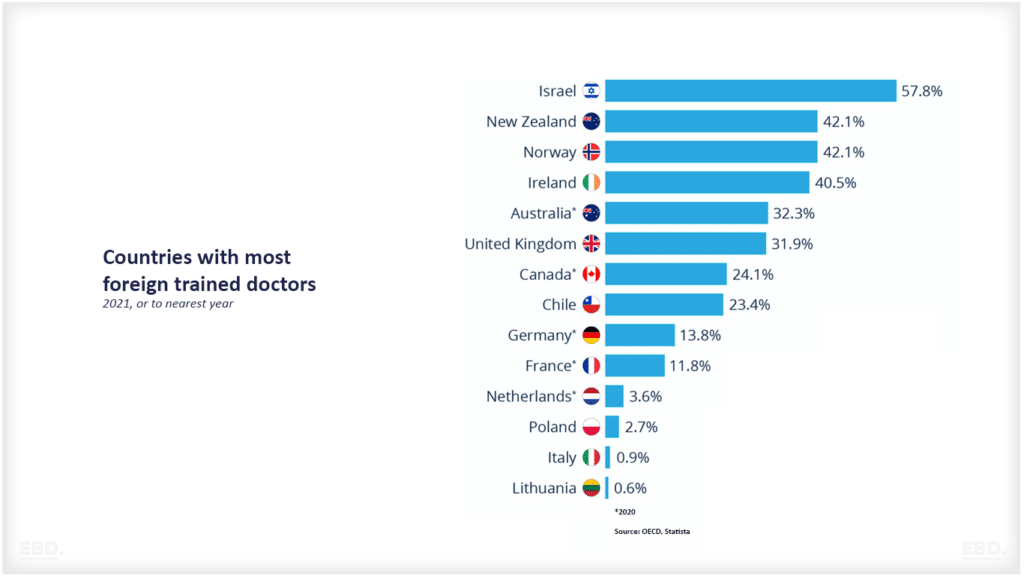

- Consider a balance between system transformation (population health management, care delivered closer to patient etc); redesign in key areas (cancer, mental health, urgent care etc); and enabler programs (growing your own staff, international recruitment, leadership etc)

- Secure investment to target at priorities.

But the approach must be hardened and turbo-charged NOW, if we are to save organisations and systems from allowing the short-term finance needs of the organisation to swamp the needs of the staff that deliver care – and from damaging the long-term financial needs.

Workforce plans will need to be real. They need to set out a future that is needed, and they must then be discussed robustly amongst executive teams, so that the difference between what is needed, and what is affordable can be understood AND ADDRESSED. Not swept under the carpet like something that will solve itself – because the result of that is just damage to staff, damage to the long-term financial stability of the organisation and a reduction in the amount and quality of care.

That won’t be an easy conversation, but by planning the way to address the gap (like turbocharging redesign (see below)) may just create a vision that can bridge the gap.

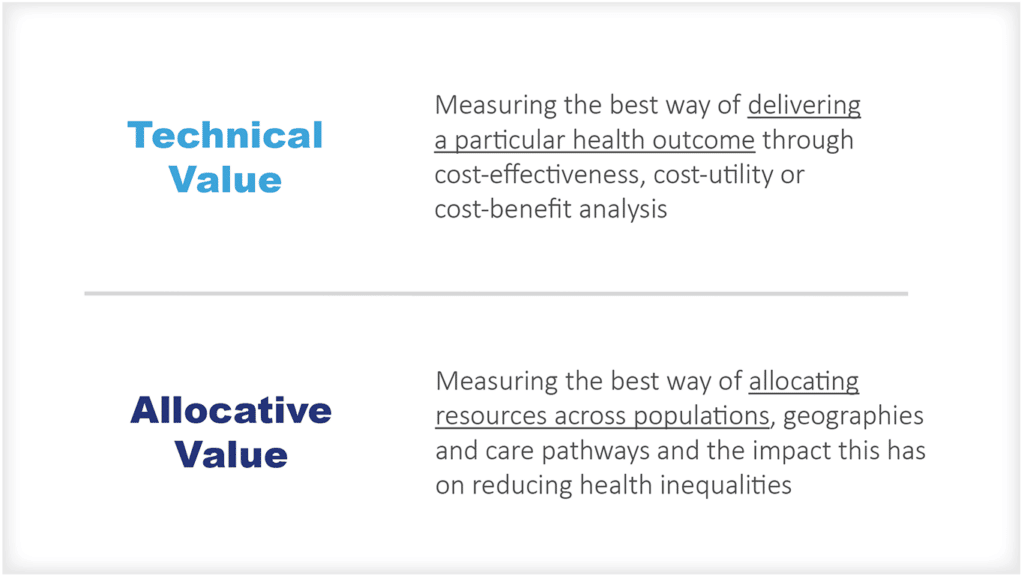

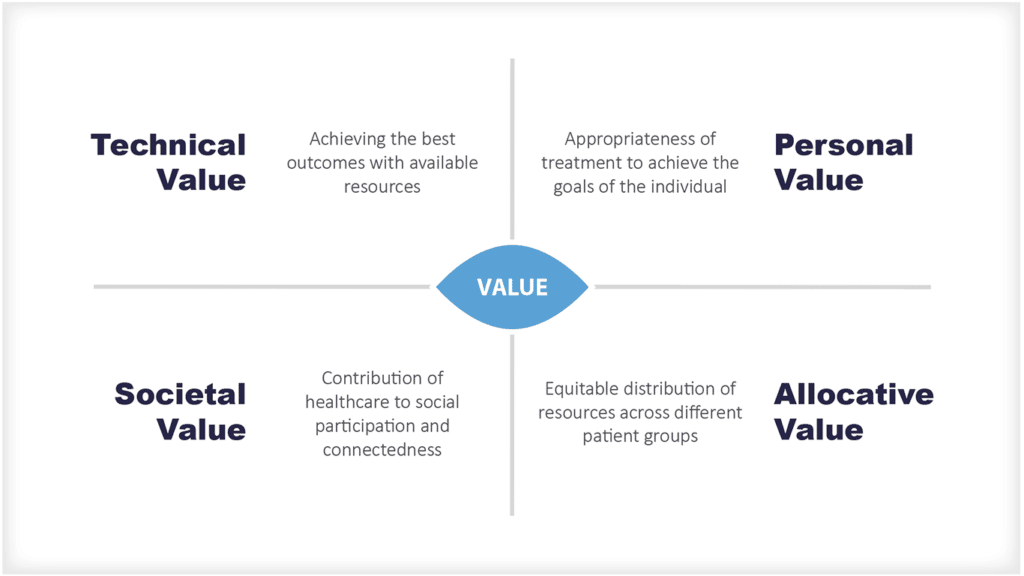

Step 2: Demonstrate the economic value of the health workforce

In days of staff cost control, we see vacancies as a blessing – some money saved to offset budget overspends. But what does that say? That staff is cost, and if we had fewer people, we’d be all right – as if actual healthcare just happens, by magic. The reality is that the value of staff is in its efficient and effective delivery of required health and care and the valuable activities that surround it. Only by existing and delivering can it have value, and we need to do a better job of assessing and celebrating the value, as well as understanding its cost in a much more mature way.

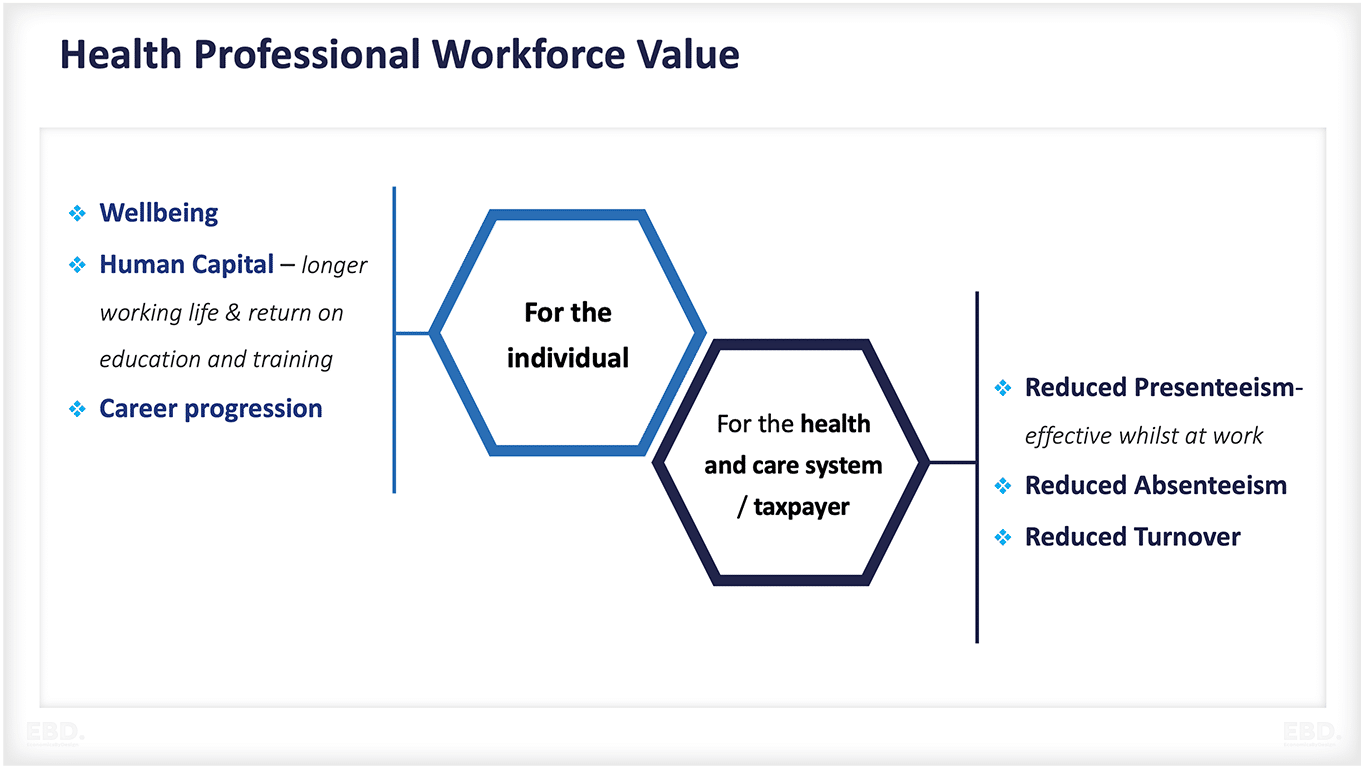

We need to recognise the full value of working in the NHS to our workforce, and recognise the value of our workforce to the NHS .

The true cost of healthcare staff isn’t in how much we pay people, it is in all the money that is paid for the activity that is not efficient or required. If we wanted metrics that accurately identified staff cost, we would look at:

- Cost of time wasted on activities that aren’t valuable

- Underperformance – more time overall spent on delivery care than is optimal to produce the best value

- Cost of career changes – due to people leaving for sub-optimal reason

- Vacancies and sickness – because that would mean that value is not being added.

- Presenteeism – people turning up to do work that is not actually advancing the patient and thus adding value

- Cost of people dropping out of training courses because they haven’t had a good experience

- Cost of people leaving because management hasn’t inspired them etc.

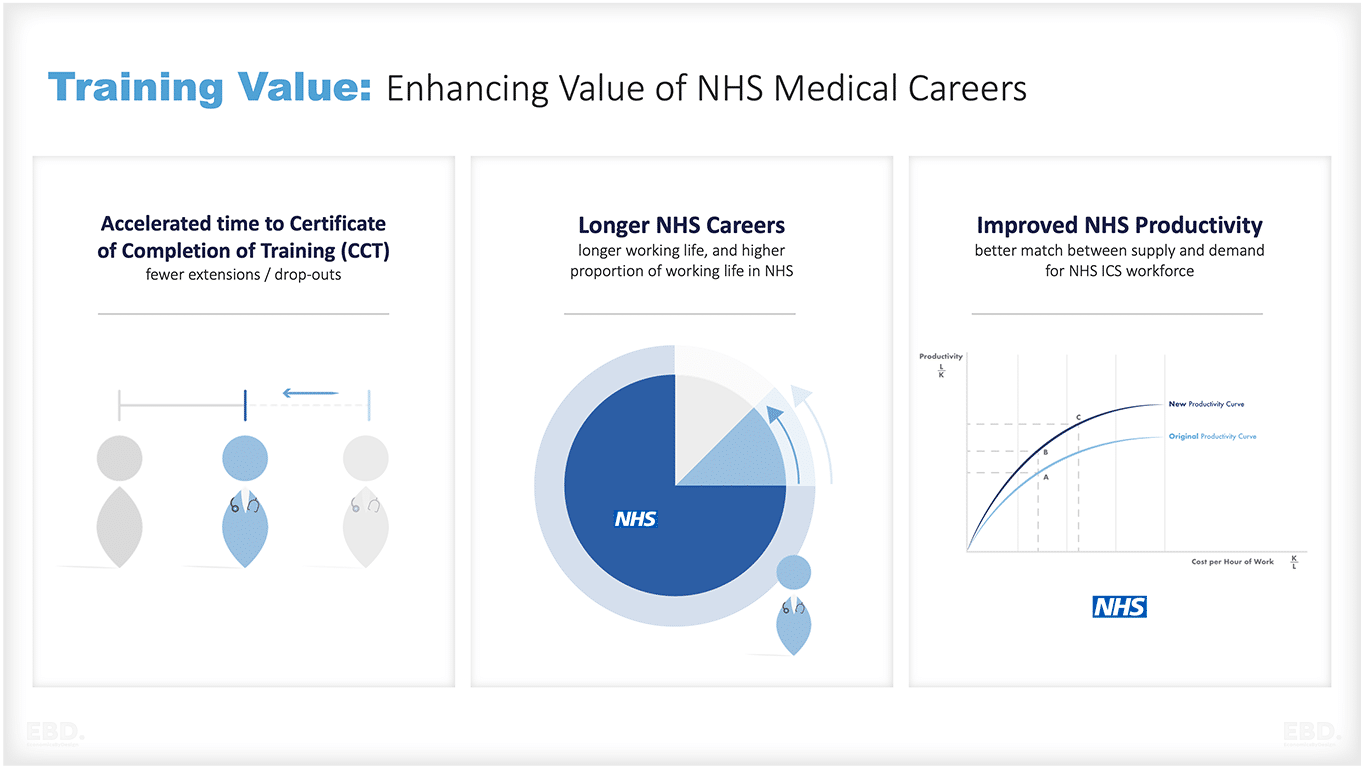

Our national strategic workforce planning needs to incorporate the value of investing in system wide programmes which accelerate time to train, extend careers and in particular NHS careers, and which improve productivity because people are working to their scope of practice and experiencing high levels of wellbeing at work.

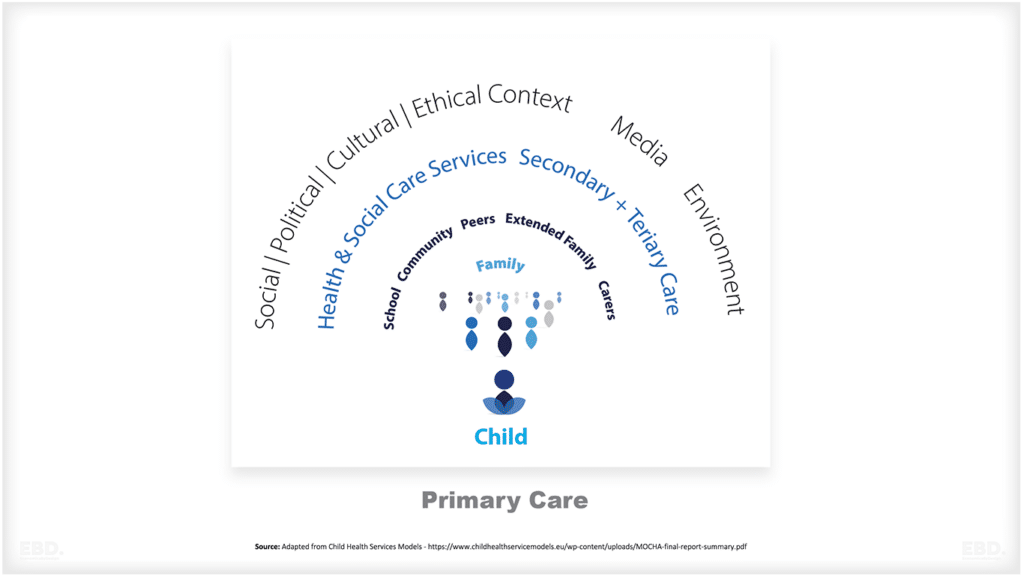

Our workforce plans should include strategies for investing in the competencies that are needed for integrated care such as patient advocacy, effective communication, multi-professional teamwork, people centred care and continuous learning. We should be including workforce transformation strategies in our workforce plans such as:

- upskilling the health workforce, including doctors (generalists and specialists), nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacists, other allied health professionals, and community health workers.

- task shifting—extension of the scope of practice by drawing on the wider health workforce to take on tasks previously the domain of medical professionals

Without our workforce our ambitions for integrated care will come to nothing.

Step 3: Invest in Appreciative Leadership

Even before this problem, we would have argued that a focus on real leadership and management skills in healthcare is the single best investment that could be made. High performance, great levels of care, reduced waiting lists, lower costs and higher morale flows from the quality of the leadership and the management in teams, organisations and systems.

Now, with staff having many more options, will require this to be turbocharged – and systems will need to value their people. Appreciative leadership is one way to do this.

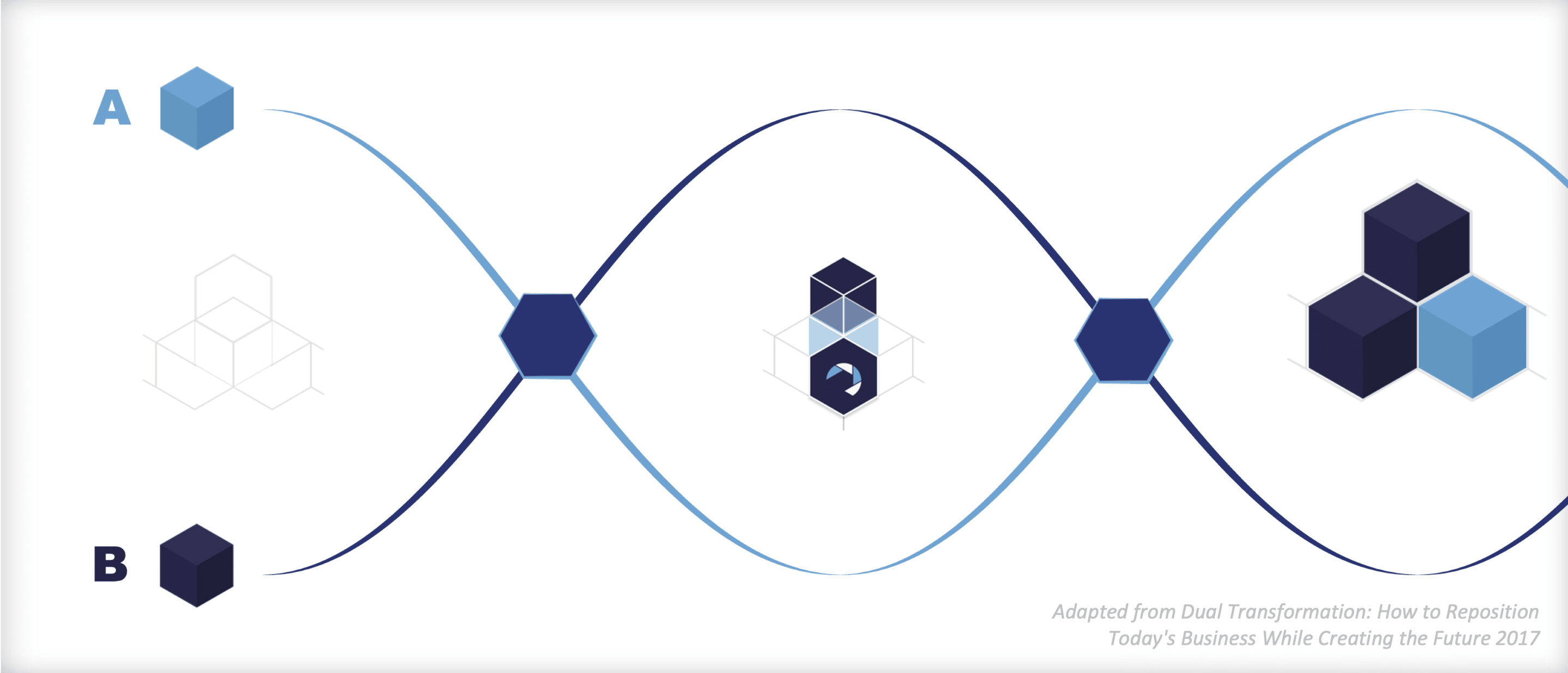

Step 4: Dual Transformation

We were already seeing the redesign challenge in health and care outstripping the supply of time, people and skills to be able to deliver it. The lack of proper system working, the high workloads and relatively unstructured investment in redesign have led to a world in which transformation is needed across health and care systems. Now, things are much worse.

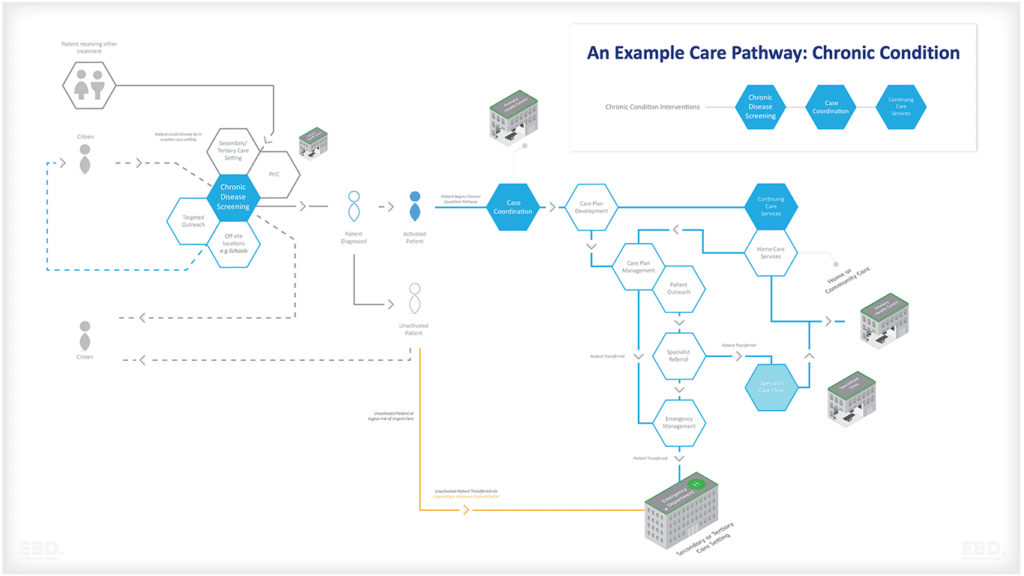

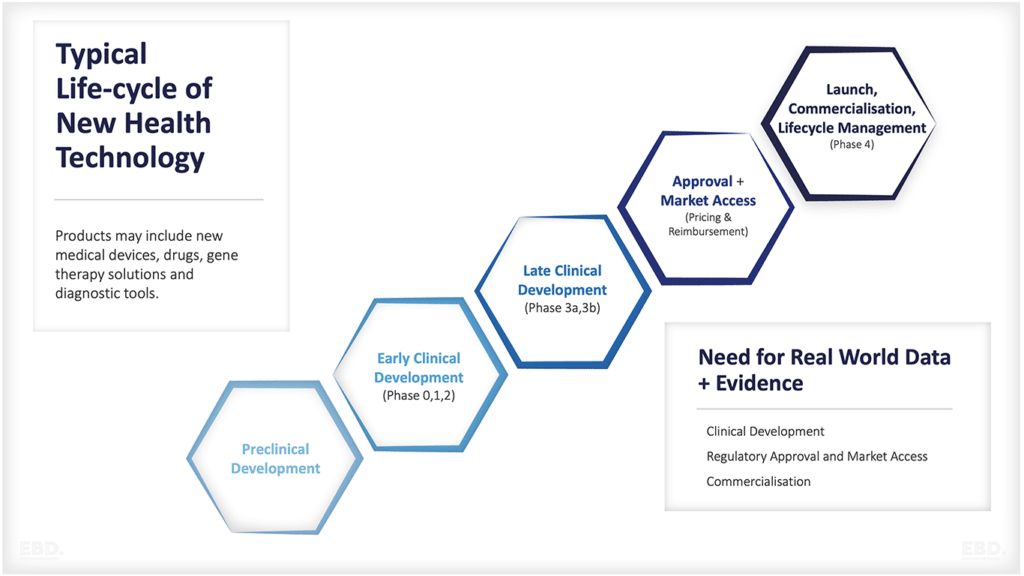

A focus on population health, lean digital systems (still with a human element), movement of some elements of care out of secondary care, community teams, greater self-management, use of wearables and genomics etc. need to be quickly worked through and brought into being to address the health and care challenges of 2022 and beyond. But it is going to have to be done properly and will take time.

In the meantime, there are a large number of innovations in care models, workforce models, technology and other areas that need to be implemented quickly in teams and organisations. We need a system of dual transformation, where teams are given the skills, permission, structure, and time to innovate within a framework that protects current practice, fairness, safety and prudence.

Step 5: The Rules of a High-Activity World

Doing any sort of workforce redesign is tough at the moment with demand massively outstripping capacity. The result is huge pressure on staff, leading to moral injury and a vicious circle in which staff leave or are ill, which puts more pressure on those left.

Just asking people to spend time embedding innovation, going on leadership development courses, and leading system redesign programmes whilst they also deal with enormous demand pressure is not going to work.

We need to set the rules for the world where demand outstrips supply – we can’t always be putting development on the back burner because we need to deliver a vaccination programme by the New Year, or because just this patient must be seen.

There are going to be more crises. There are going to be people who really should have received care by now, queuing at the gates. But by constantly dealing with the short term, we are imperilling the long-term. It should not be up to staff to make all the decisions on what is, essentially, rationing of healthcare – if we ask that, then we risk damaging and losing those people.

Final Reflections – a cup half full…

No problem is insurmountable – we just need to focus on real discussions about the number of staff we have, on understanding the immense value they create in meeting the need for health and care, and on monitoring and rewarding that rather than seeing them as a cost.

Rarely, though, are the skills of workforce planning and workforce economics combined. This presents a real opportunity for systems to design value into their workforce plans from the very start.

By treating the workforce as an asset rather than a cost, health and care systems can translate health need and triple aim goals into a statement of workforce demand which goes beyond traditional practice and uni-professional headcounts.

That was a real good read this afternoon. Thanks so much – inspiring. Triple value vs cost. So right.

Let’s hope others are listening as the key challenge is not wait lists or supply chains (yes they are real) but workforce. The pandemic de-values our workforce! Yes they responded with creativity and passion but out of place. Now there is a huge problem with burn out and loss tonprofessiona especially STEM and women.

There is a big space for technology. Like you I am a BIG FAN of wearables. But we need to innovate pathways that use them, value their champions and founders and keep knowledge about what works why / where and with whom.

Compassionate leadership was lacking. Let’s not make the same mistake in the next crisis.

Hi Adrian

Thanks so much for your comment. It is almost an embarrassment to me how little focus economists like myself have given to workforce value and how to leverage it. Your point about burn-out and losses to the profession are very well made. I do see digital health technology as an enabler for patients and staff, most especially staff. We can design workforce models which focus on leveraging this value – all we need is the complement existing good practice with an economic lens.