Climate Adaptation

In this article, we look at the Economics of Climate Adaptation, and in particular, the actions being taken by the UK.

In an accompanying article, The Health Economics of Climate Change, we take a closer look at the impact of climate change on health and the health economic issues this presents.

What is the Experience of Climate Change in the UK?

This summer, on 19th July 2022, a new UK temperature record of 40.3C was set in Coningsbury, Lincolnshire, breaking the previous record by 1.6C. A (‘minimum’) overnight temperature of 25.8C was provisionally recorded in Kenley in Surrey, again breaking the previous UK record by 1.9C.

Since records began in the late nineteenth century, the top 10 recorded warmest years have all occurred since 2002 – the decade to 2019 was the warmest. Looking further back, the average surface temperature in the UK has consistently risen, now over 1C higher than about 100 years ago.

There is consensus that this trend will continue, with temperature, compared to the late nineteenth century, set to rise by 1.5C by mid-century at best, and potentially by up to 4 or 5C by the end of the century in extreme case scenarios. And, with the heat comes a whole bunch of other climate hazards which include water shortage (in some places), sea level rise, wetter winters, and increased incidence of storms and flooding.

Download the Met Office UK Climate Projections database to explore climate predictions to a 2.2km scale.

What are the Consequences of Climate Change in the UK?

There will be opportunities for the UK from climate change. Warmer winters may sound quite appealing at this moment as we look forward to a winter of high energy bills and may fear the emergence of infectious diseases that enjoy our colder season. There may be economic advantages, for example, in attracting tourism and from extended growing seasons.

Overall, however, the evidence indicates that the costs of climate change to the UK exceed the benefits.

Climate Change Risk Assessment

Every five years, the Climate Change Act 2008 requires that a Climate Change Risk Assessment is undertaken. The recent Climate Change Risk Assessment (no. 3) represents a very substantial body of evidence and identifies 61 broad risks and opportunities from climate change in the UK, of which over 50 are risks.

These cut across all sectors of our economy, and include impacts on health, the natural environment, infrastructure, and business, as well as risks that are international, such as impaired food supply chains or challenging migration movements.

For 8 of the 61, UK economic damages by 2050 under a 2C warming scenario are estimated to exceed £1bn p.a. This rises to 15-20 risks if a higher global warming scenario is assumed. The number of risks falling into this ‘very high’ damage category has risen since a similar assessment in CCRA1 a decade ago, which found only three risks this large.

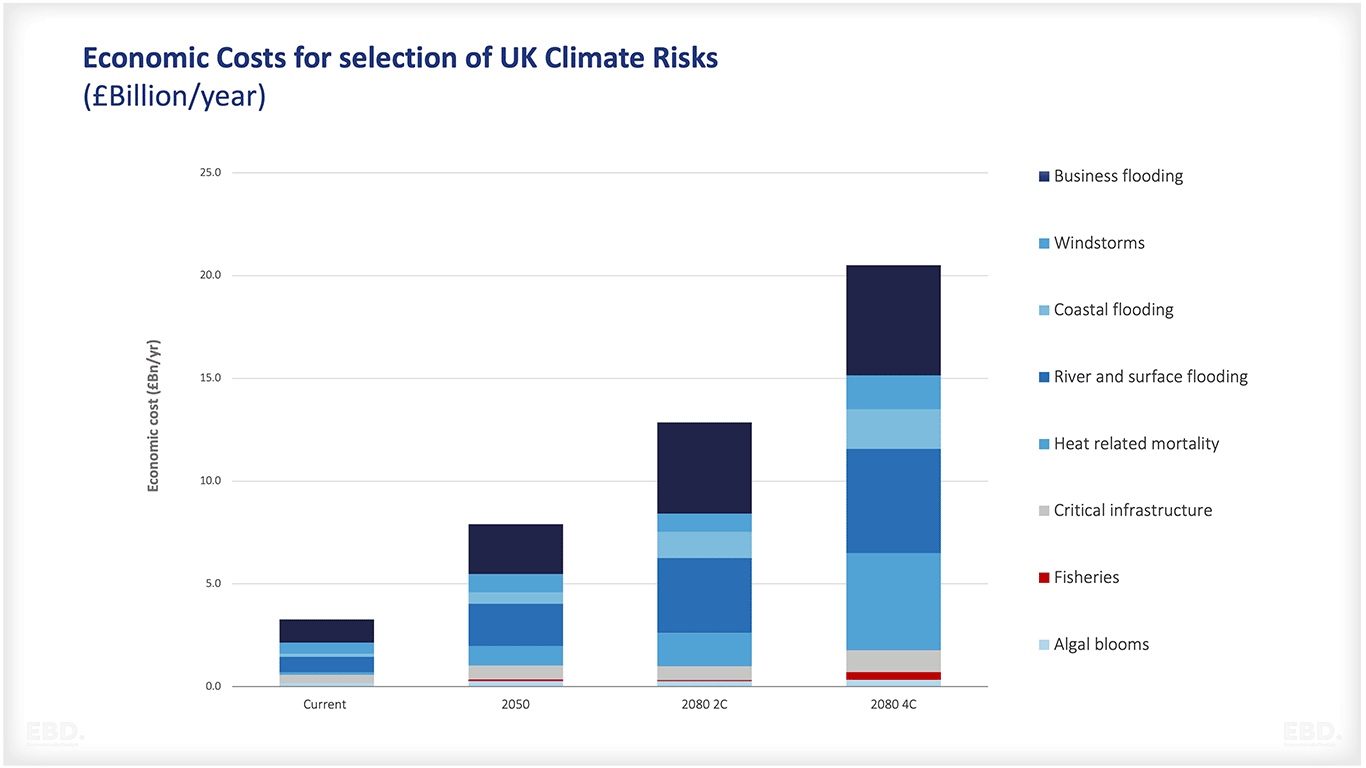

For 36 of the risks, UK damage costs are estimated to be at least £10mn p.a. Major risks include coastal, river and surface water flooding including direct costs (e.g. damage to property) and indirect costs on businesses, supply chains, etc. A selection of individual risk estimates is shown below, with economic cost data, drawn from CCRA3 outputs.

Annual economic costs of climate change in the UK for a selection of risk. Values include the climate and socio-economic change, presented in current prices with no discounting. Source CCRA valuation report

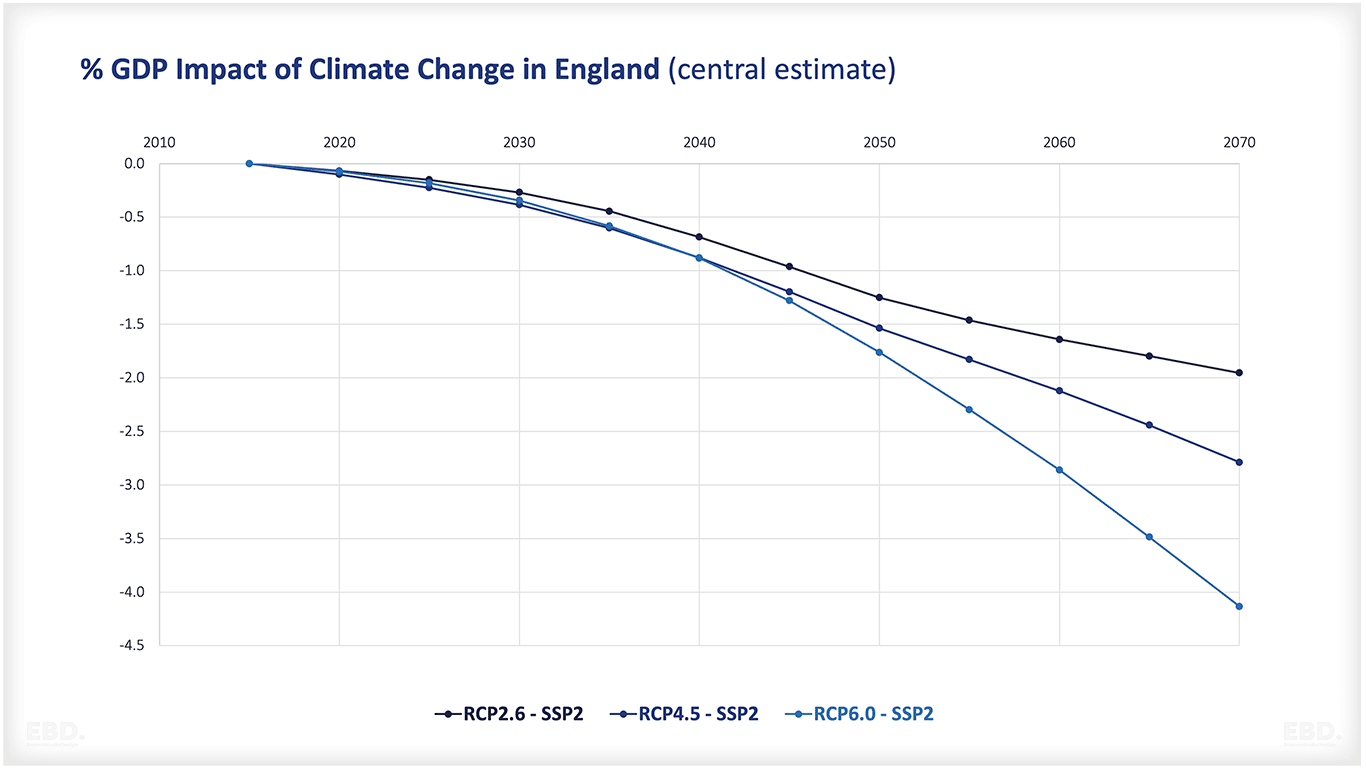

Recent international modelling work from COACCH (CO-designing the Assessment of Climate Change costs) estimates economic costs to the UK, in aggregate, could be >1 to 1.5% of GDP/year by 2045 (central estimate). They rise significantly in later years, especially if the Paris Goals are missed – the Paris Agreement (2015) is an international treaty on climate which included commitments to contain climate change, preferably to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

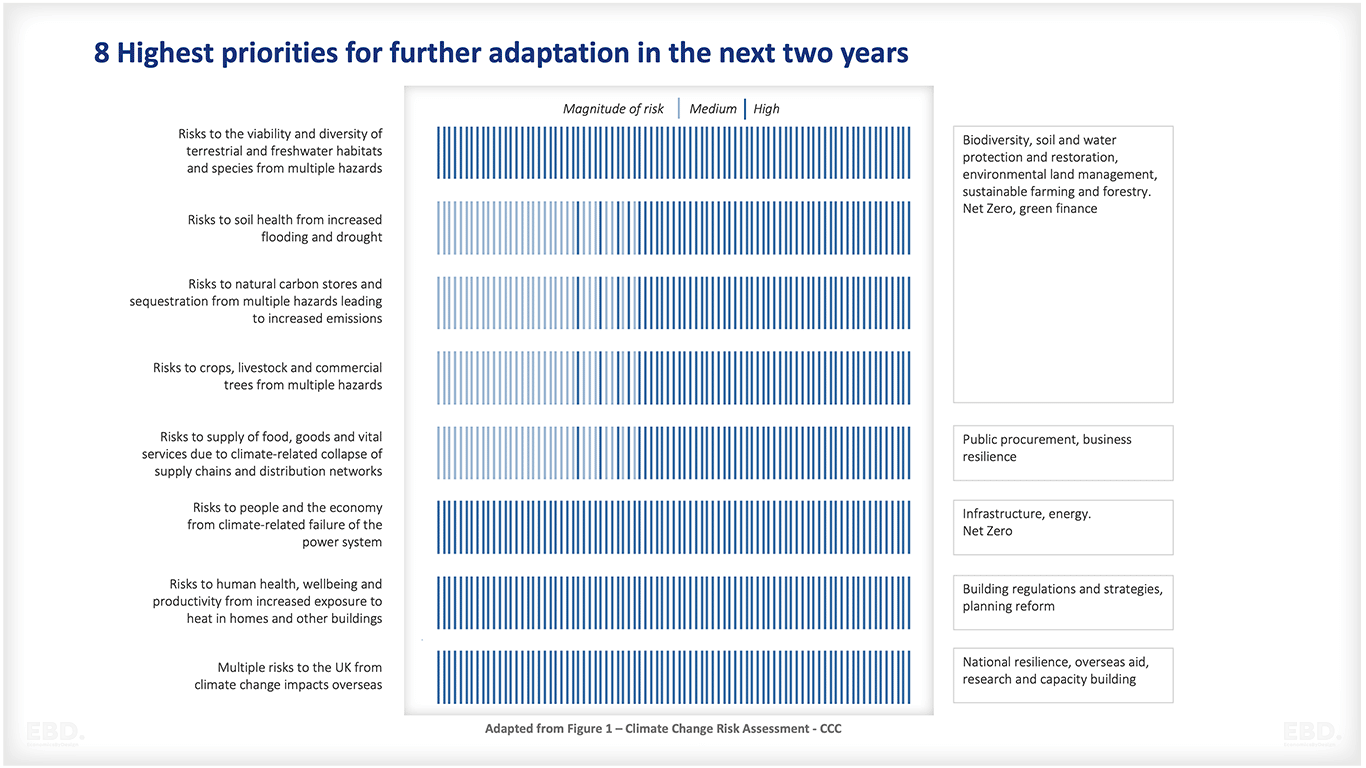

The CCRA also undertook a qualitative expert-driven assessment of the need to take further action across the 61 risks and opportunities.

It finds, that of the 61, 34 are classified as ‘more action needed’, meaning that new stronger or different action is required in the next five years over and above those actions planned.

8 priority risks have been identified, where there is an opportunity to act in the near future, summarised in the CCRA ‘Advice report’.

These are set out in the figure below:

- Risks to the viability and diversity of terrestrial and freshwater habitats and species from multiple hazards

- Risks to soil health from increased flooding and drought

- Risks to natural carbon stores and sequestration from multiple hazards leading to increased emissions

- Risks to crops, livestock and commercial trees from multiple hazards

- Risks to supply of food, goods and vital services due to climate-related collapse of supply chains and distribution networks

- Risks to people and the economy from climate-related failure of the power system

- Risks to human health, wellbeing and productivity from increased exposure to heat in homes and other buildings

- Multiple risks to the UK from climate change impacts overseas

Download the 3rd Climate Change Risk Assessment which includes a detailed assessment of each risk, an economic analysis of climate risks, a summary report and UK national and sector summaries.

What Can Be Done to Reduce the Risks of Climate Change?

There are two broad approaches to climate change. The first is to prevent it, by reducing climate emissions – this is known as climate mitigation. The second is to adapt and prepare for climate change – this is known as climate adaptation.

Economics of Climate Mitigation

The UK has an ambitious target-driven approach to reducing climate emissions produced by the UK. This is to achieve Net Zero emissions of GHGs by 2050 which will be achieved by a combination of measures to reduce GHG emissions such as reducing energy demand by insulation of buildings, developing alternative energy supplies that don’t burn carbon, and electrification of transport, and measures to sequester (take out) GHGs from the atmosphere, such as planting trees and restoring peatland which absorb carbon dioxide.

The UK strategy for addressing climate mitigation is summarised in the Net Zero Strategy, published in October 2021:

However, as we know, climate change is a global phenomenon and what we do in the UK cannot directly impact the trajectory of climate change in a large way. From a climate perspective, the case for the UK to pursue NZ is primarily how this path of action may lead the world and inspire others to do more – there are other rationales for decarbonisation, including economic and political opportunities.

Also, as illustrated in the Figure above, much of the climate change we will see in the next twenty years is already locked in – i.e., it (and the associated costs) will happen whatever we do to reduce emissions. From a climate perspective, climate mitigation is primarily about what happens after that and whether global temperatures rise by 2 degrees or 4, with significantly greater costs (and some consequences we don’t fully understand).

Economics of Climate Adaptation

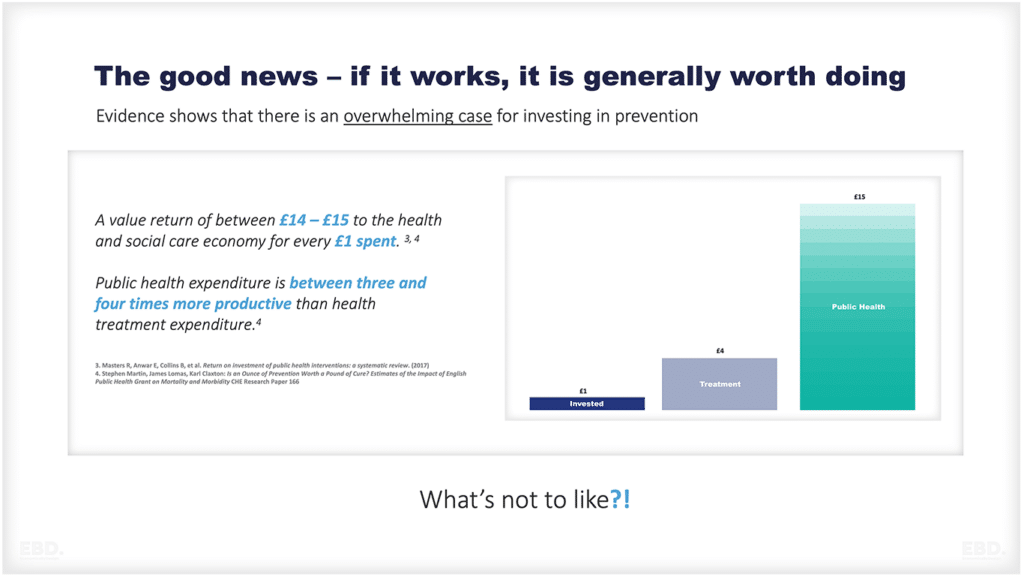

The other broad approach to climate change is to accept that it will happen (to some degree) and prepare for it. There is a lot that can be done and the economics of adaptation, whilst limited in scope, is nevertheless very persuasive.

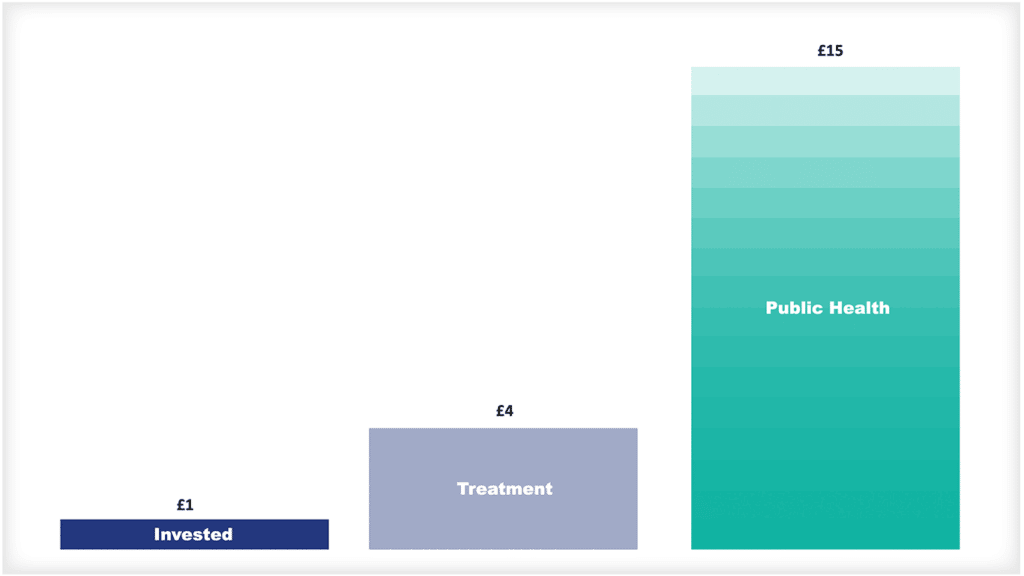

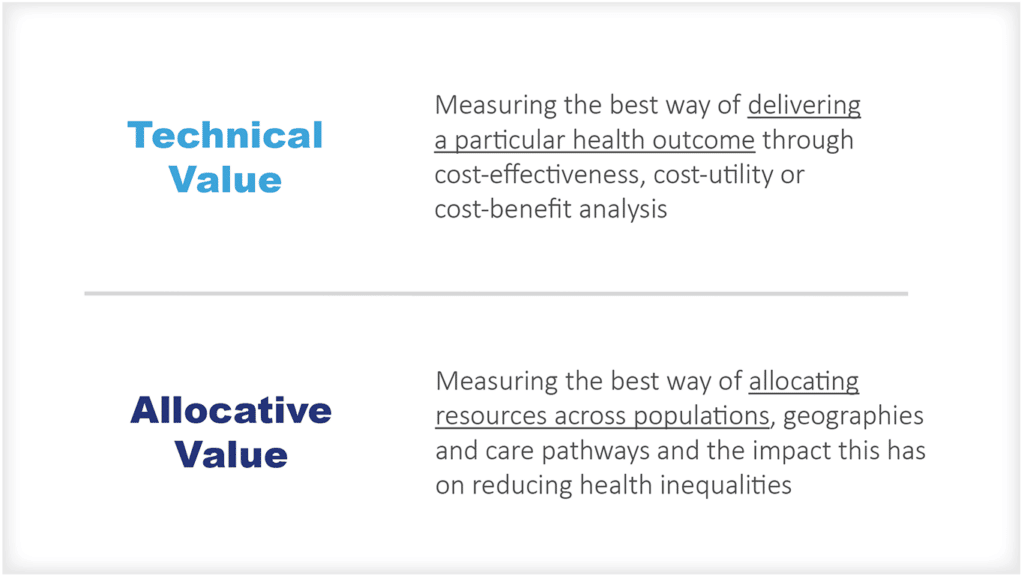

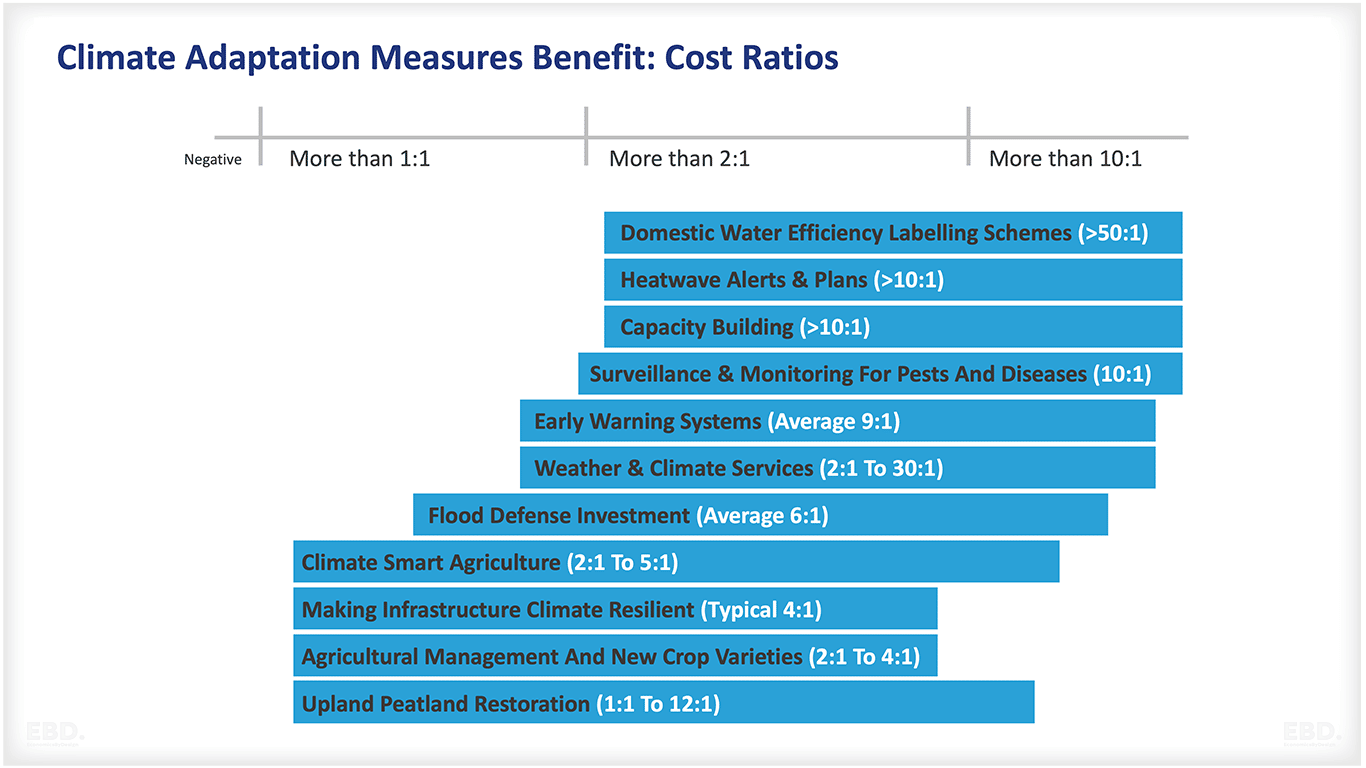

Many early adaptation investments deliver high value for money. The CCRA3 undertook a review of benefit-to-cost ratios for a range of early interventions. These are summarised below. The benefit-cost ratios typically range from 2:1 to 10:1 – i.e., every £1 invested in adaptation could result in £2 to £10 in net economic benefits.

There is a particularly strong case for so-called low regret interventions that come at low cost – this includes non-technical interventions that involve monitoring risk, collecting information and developing plans for responding to climate events.

There is a strong economic case also for interventions where there is a risk of lock-in. This applies to assets that have long lives, such as buildings and infrastructure, where the cost of designing-in climate-proofing is lower than retrofitting subsequently.

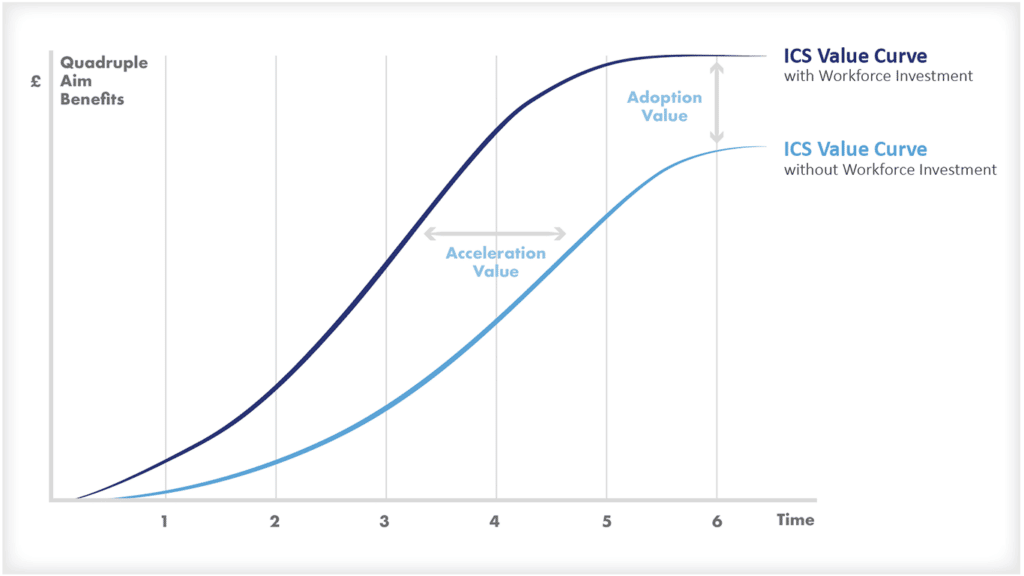

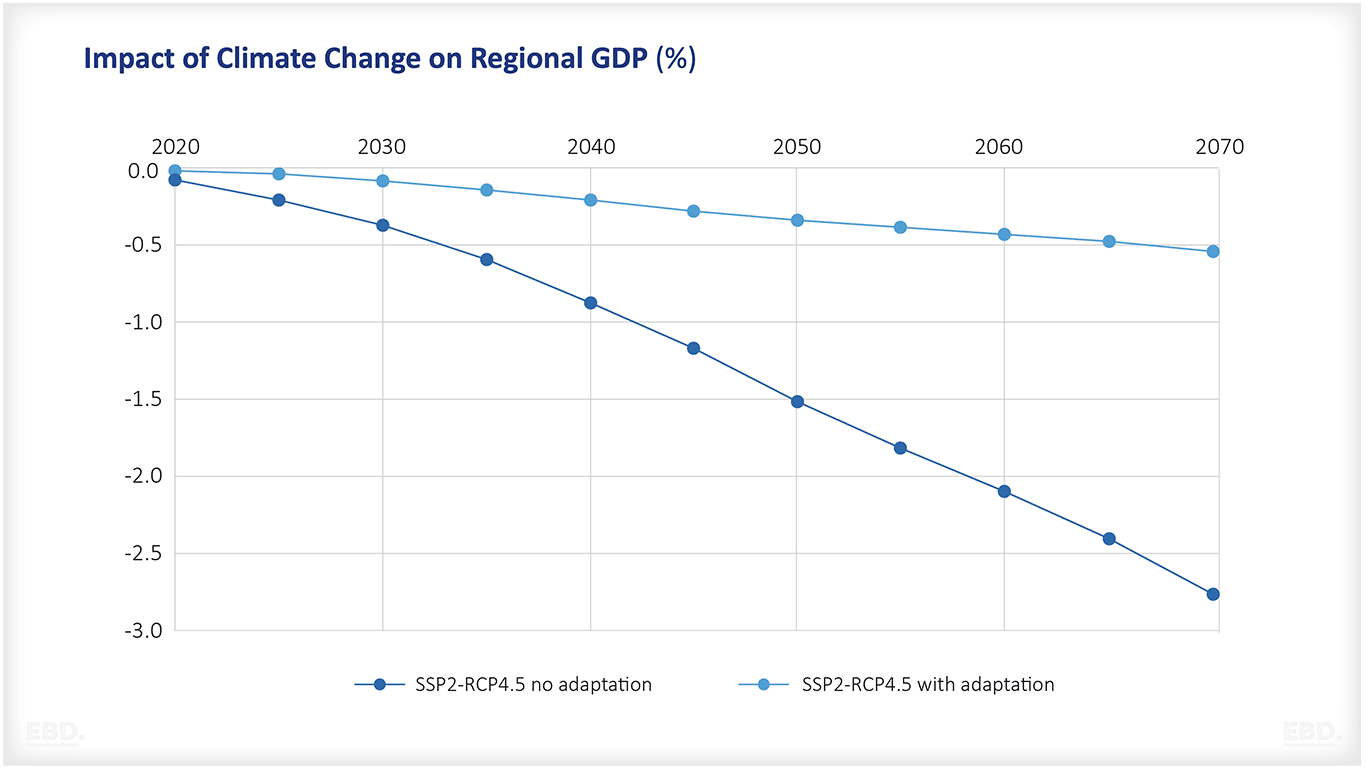

Other research, illustrated below, has shown that adaptation measures can dramatically reduce the aggregate costs of climate change.

There is a particularly strong case for so-called low regret interventions that come at low cost – this includes non-technical interventions that involve monitoring risk, collecting information and developing plans for responding to climate events.

There is a strong economic case also for interventions where there is a risk of lock-in. This applies to assets that have long lives, such as buildings and infrastructure, where the cost of designing-in climate proofing is lower than retrofitting subsequently.

Other research, illustrated below, has shown that adaptation measures can dramatically reduce aggregate costs of climate change.

What are the Barriers to Adaptation?

Given the strength of the evidence, it is an important question to ask why adaptation is not occurring as the CCRA might hope, and what are the barriers. Given the number and breadth of climate risks, there are a lot of answers.

Barriers include:

- gaps in data including on local risk and indicators of success where objectives are hard to define,

- absence of clearly identified risk owners and victims and the necessary incentives for action,

- issues of governance where adaptation involves multiple actors including at the national and local levels, and

- challenges managing risk (vs certain outcomes) and risk into the future whilst decision-makers may focus on the near-term.

The prevailing approach to adaptation is not to treat it as a discrete objective but to embed as a cross-cutting concern that affects multiple decisions in varying contexts.

There are lots of circumstances that you may ask ‘have you taken climate into account’ – this is true, for example, in many hospitals that are subject to high levels of overheating which poses risks to staff productivity and the health of the vulnerable. Embedding seems a sound approach, but at the same time, embedding means climate may be a secondary issue, and it may be harder to drive forward in a world of competing pressures.

In health care, there is an established debate between the respective benefits and balance of prevention and treatment. Often it is found that it is economically best to prevent though we may spend most resources on treating it. In climate, there is also a case for mitigating (preventing) and adapting (treating) in combination. But, perhaps, unlike in health, we are in a position where we can give more attention to some good value options for treating the problem.