Economic Efficiency

According to Wikipedia, efficiency is “the (often measurable) ability to avoid wasting materials, energy, efforts, money, and time in doing something or in producing the desired result” [1].

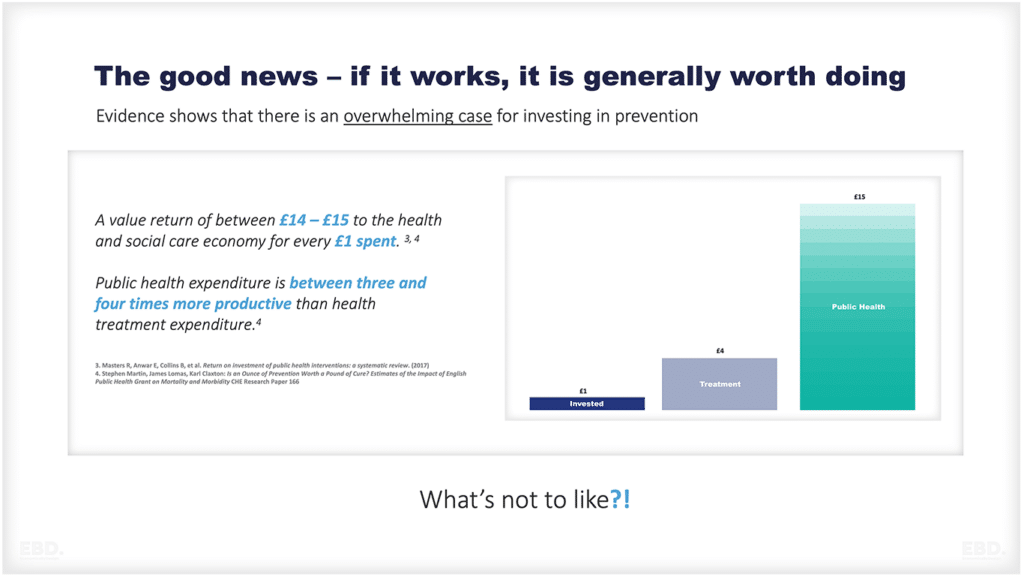

From an economics perspective, economic efficiency improvement is always, and everywhere, a good thing. How can it be otherwise?

Wasted resources mean that someone somewhere is losing out – either the patient, a community, or the taxpayer. Working in integrated health systems where waste is ignored or endured is demoralizing for staff too, especially when it impacts on their ability to perform at their best.

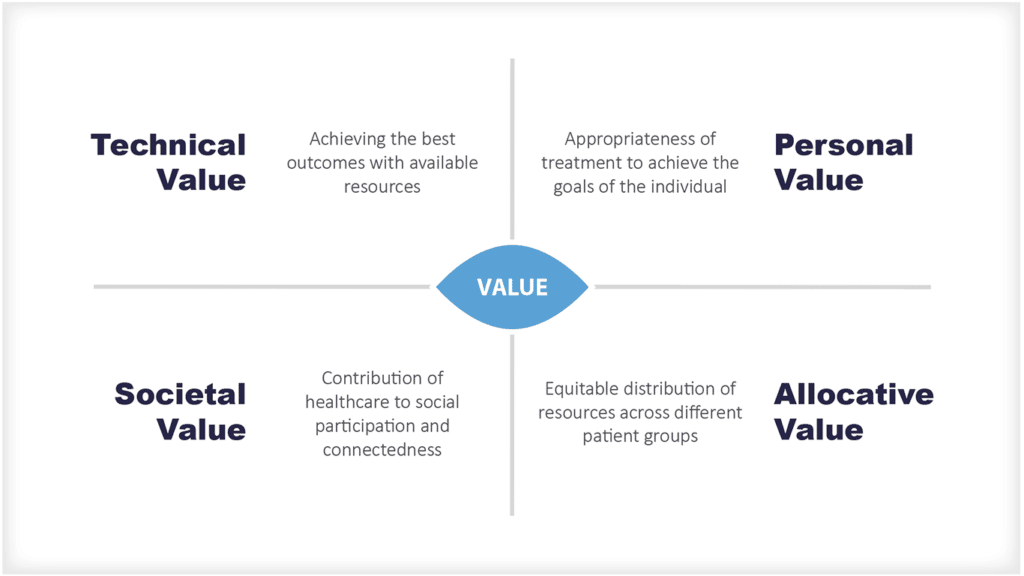

Health economists tend to look at improvements to health system efficiency as being a positive measure of economic value.

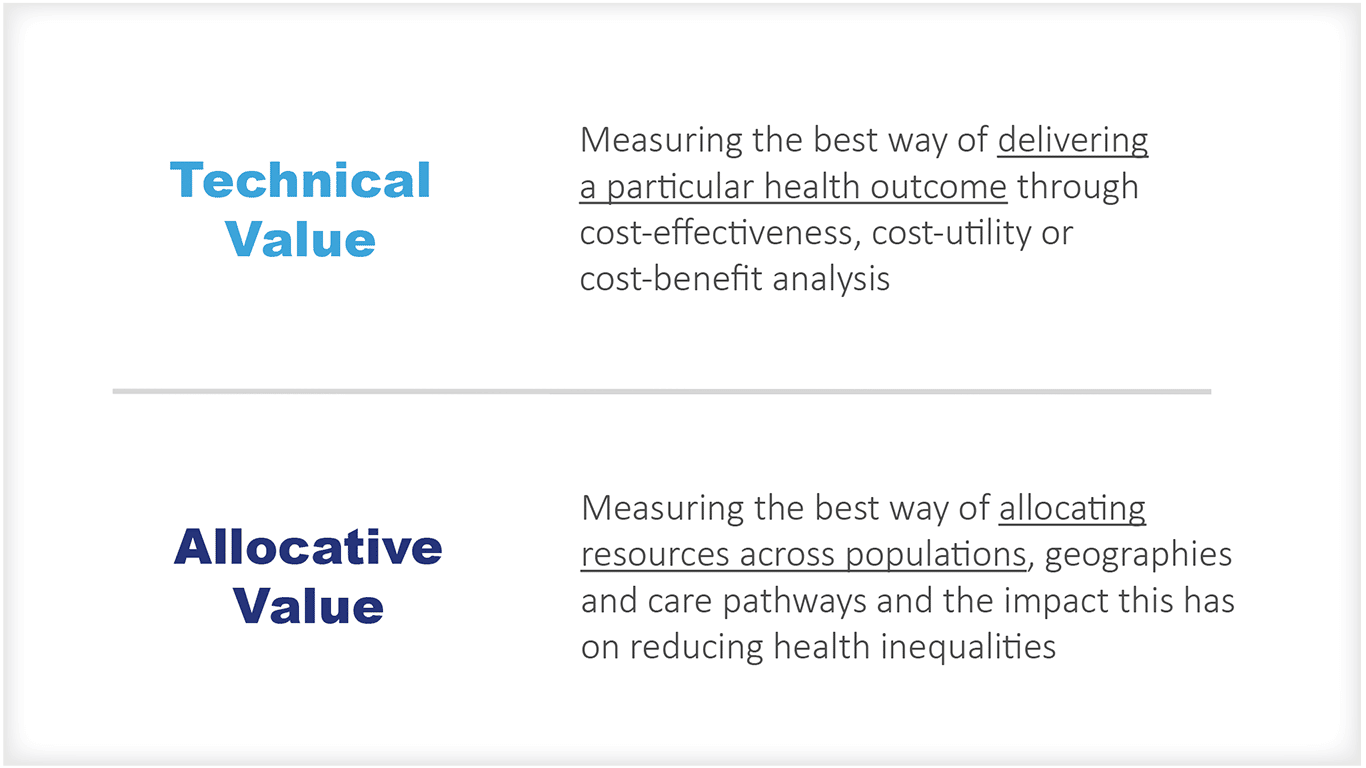

There are two main types of efficiency:

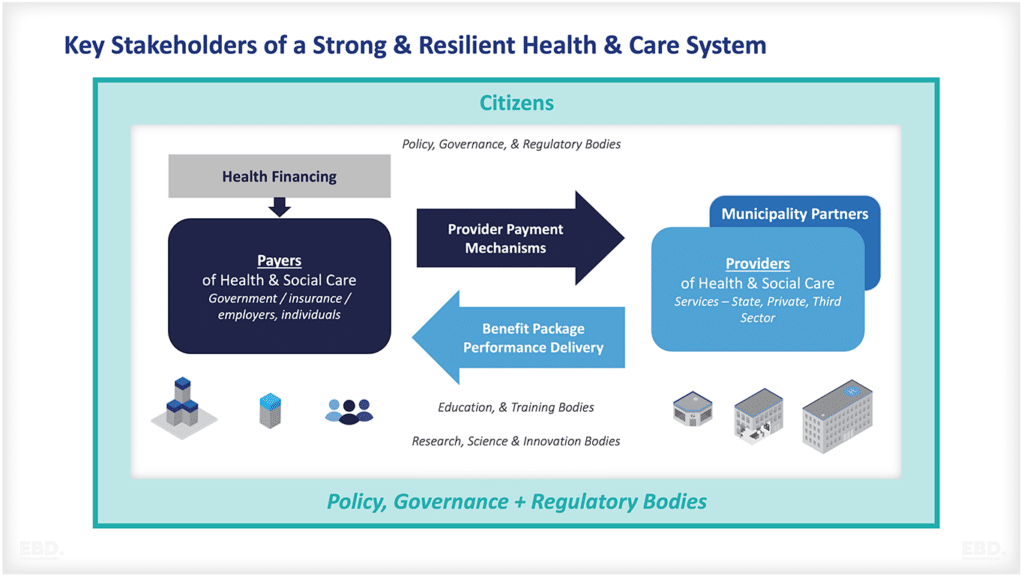

Health System

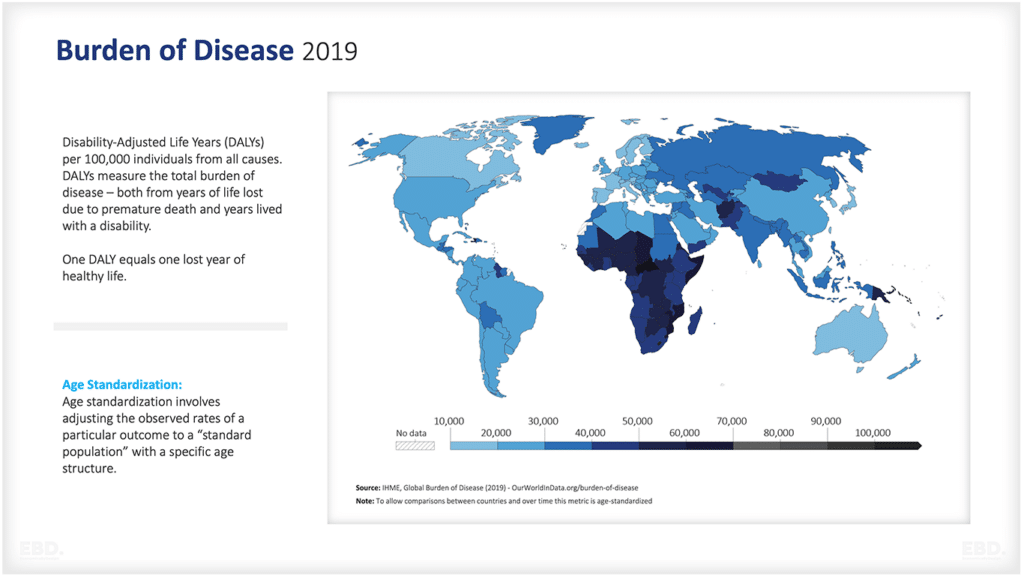

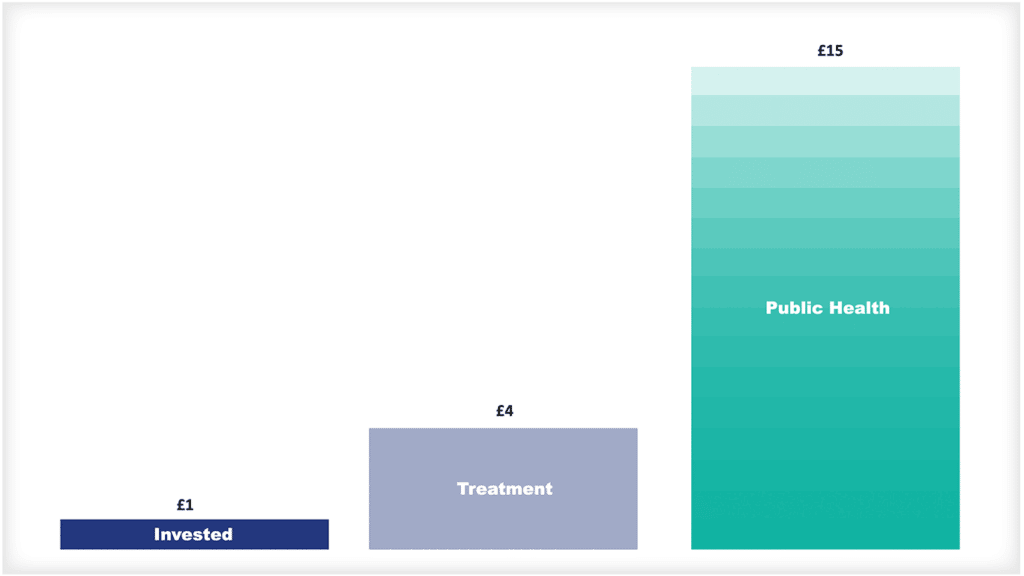

Opportunities to improve efficiency exist where changes can be made to the use of resources to improve health outcomes or reduce health inequalities.

For government-funded health services, efficiency targets are set to drive reductions in waste and to reduce the funding pressure of growth in demand (or to improve health service coverage).

Achievement of efficiency targets is often baked into funding allocations to health system payers and providers. For the NHS in England, for example, in recent years, funding has been based on an underlying assumption of efficiency savings of 1.1% per annum. In his recent Spring Statement, this target was doubled by the Chancellor of the Exchequer to 2.2% per annum.

Why then are efficiency targets often perceived so negatively? And why, when economists joyfully proclaim opportunities to improve efficiency, are such opportunities greeted with concerned frowns by those who must implement them?

Is it because efficiency, the reduction of waste, is being confused with pressure to work harder?

Is it because the efficiency target is so unrealistically high and so relentless (every year another target) that it will inevitably turn into budget cuts?

Is it because front-line health professionals are focused on care delivery, not necessarily efficient care delivery (someone else’s problem)?

Is it because it is so difficult to achieve system efficiency targets in a complex adaptive system such as health care?

Is it because inefficiency is a design feature of government-funded health systems?

I have heard all these reasons, and more, over the course of my career.

It seems to me that “low-hanging fruit” or “no regret” efficiencies that are costless and easy to implement, are usually dealt with quite successfully on a day-to-day basis by motivated teams with strong leadership. If teams are empowered and work well together, they don’t tolerate waste and don’t need efficiency targets to make the best use of scarce resources.

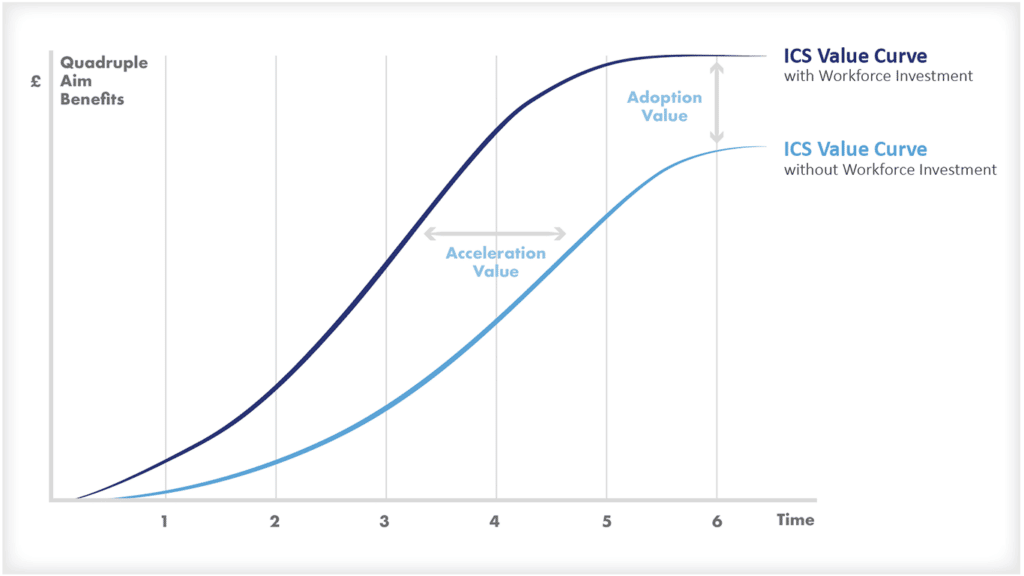

However, dealing with chronic waste at a system level is often much more difficult and requires a serious investment of time, transpersonal system leadership, and effective change management.

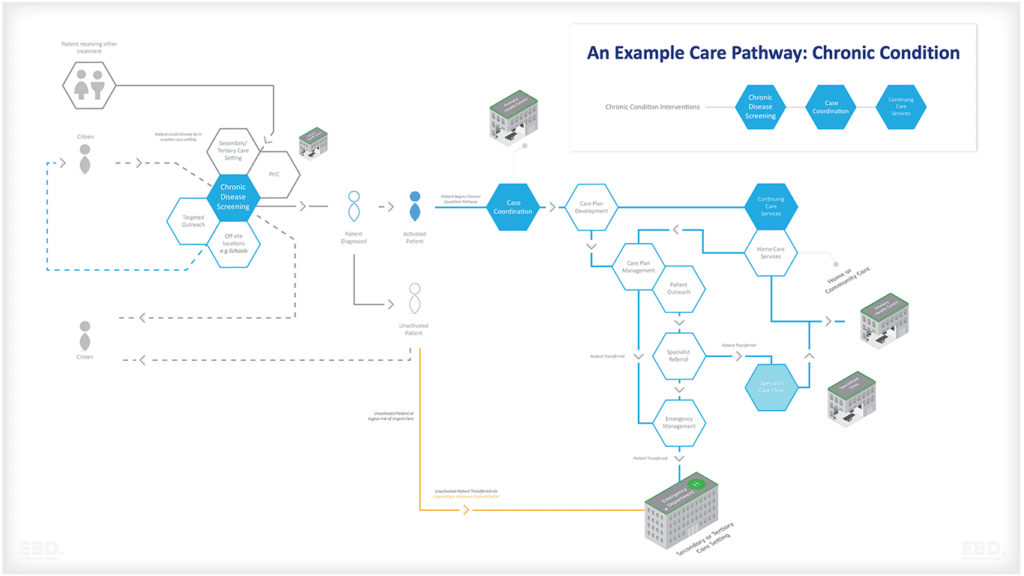

For a health system even as advanced as the NHS in England, there is plenty of evidence of system inefficiency. Setting aside data on unwarranted variation in practice [2], most of us can point to direct personal experience of a complex patient journey that has broken down across care and treatment providers, resulting in systematic duplication of resources.

Most of us involved in health system design can also point to solutions to these problems, and with strong evidence and cost-benefit analysis to support them.

There is certainly potential for the new Integrated Care Systems to be a game-changer, in terms of improving health system efficiency. Collective accountability, and collaboration across organisations and professionals, should enable some of these solutions to be implemented to improve population health and care coordination. It will, though, take time.

In the meantime, it may be that some further honesty is required about the allocation of health system funding in the short-term. The state of the economy, the pressures from tax revenues, and the priorities for spending across other parts of government all contribute to the pressure on health system budgets. However, doubling the efficiency target now risks reinforcing the negative message to staff and patients alike that efficiency = cuts. It also risks the success of the system reform itself if staff morale deteriorates.

For my part, I will continue my mission to advocate for efficiency and encourage everyone to see it as part of their role to identify and reduce wasteful use of precious health resources.