The Healthcare Workforce

The healthcare workforce is an integral part of any successful health system. There are many different professions which collectively comprise the healthcare workforce (see for example: The healthcare workforce: a simple guide. They all have skills, capabilities and competencies that reflect the bespoke education, training and continuous professional development they need to provide healthcare services commensurate to their role.

Ensuring that the education and training of the healthcare workforce is of the required standards is therefore essential to providing quality care. This economic lens will provide an overview of the key components of education and training for health professions.

What Are The Traditional Models For Health Professional Education and Training

Traditional models of education and training comprise:

- basic knowledge acquisition at school

- advanced knowledge and skills development through colleges and/or a higher education institution, often combined with experiential placements in clinical settings

- specialist knowledge, skills and capabilities through post-graduate learning, again combined with experiential placements in clinical settings

- pre and post-registration on-the-job training provided by health care providers/employers, supported by professional bodies

- continuous professional development through participation in learning events and learning experiences.

It’s a complex partnership between individual trainees, supervisors, employers, educational institutions and professional bodies. Each profession has its own unique pathway, and each country has their own practice registration requirements and system governance arrangements.

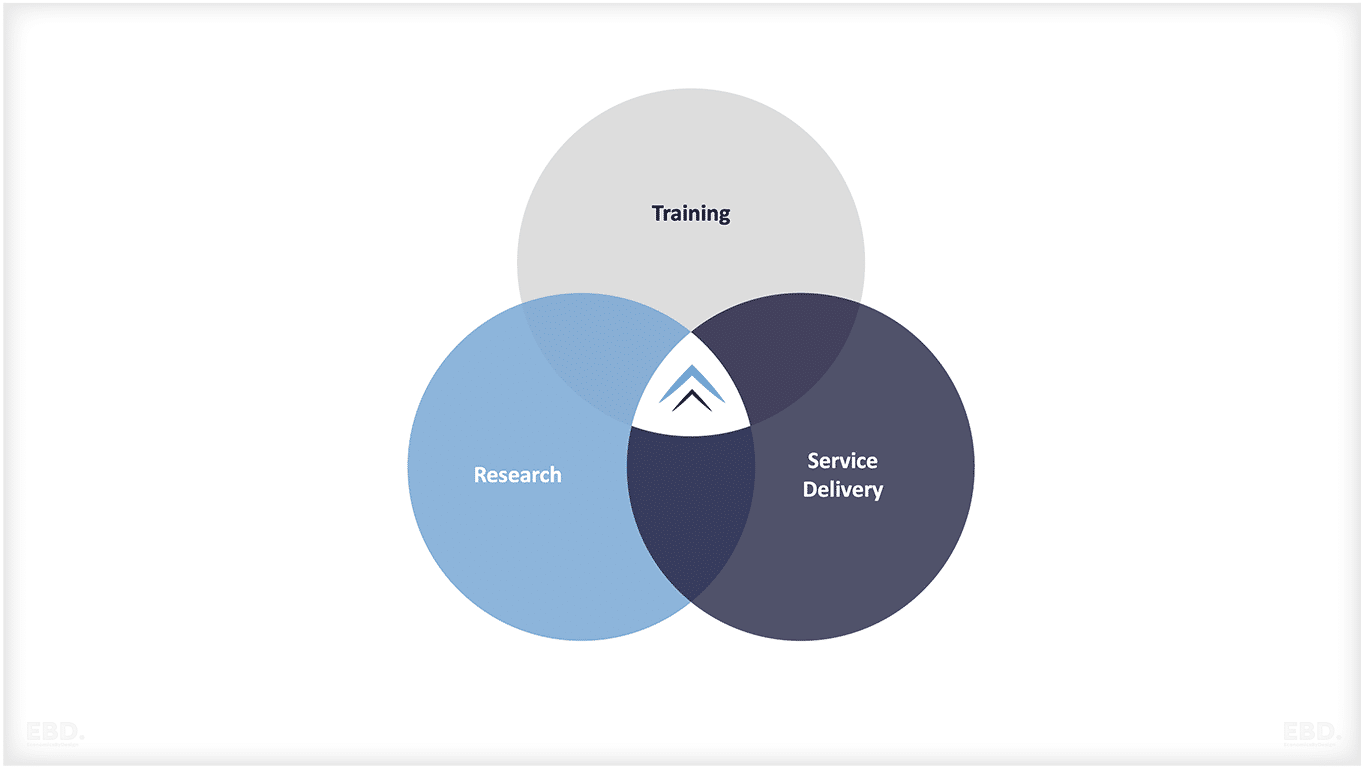

Often, institutions providing support for education and training of the healthcare workforce are also engaged in research and development. The line between service delivery, training and research can be blurred as the strong inter-relationships combine to enhance the quality of all three.

What Innovations Exist In The Education And Training of Health Professionals?

Traditional models of educating and training health professionals have rapidly evolved over the last decade. In particular, technology has enabled distance learning options, web-based learning programs, simulations and virtual reality experiences to be used to facilitate the acquisition and retention of knowledge and skills.

As integrated care systems have developed, new training programmes have developed to promote enhanced practice and advanced practice and multi-professional learning. Postgraduate degrees in advanced practice have developed covering clinical practice, leadership, management, research and education.

Increasingly, training is shifting from being undertaken solely on the basis of “time served” and instead, being based on the ability to demonstrate competency and capability.

How Does A Training Pathway Work?

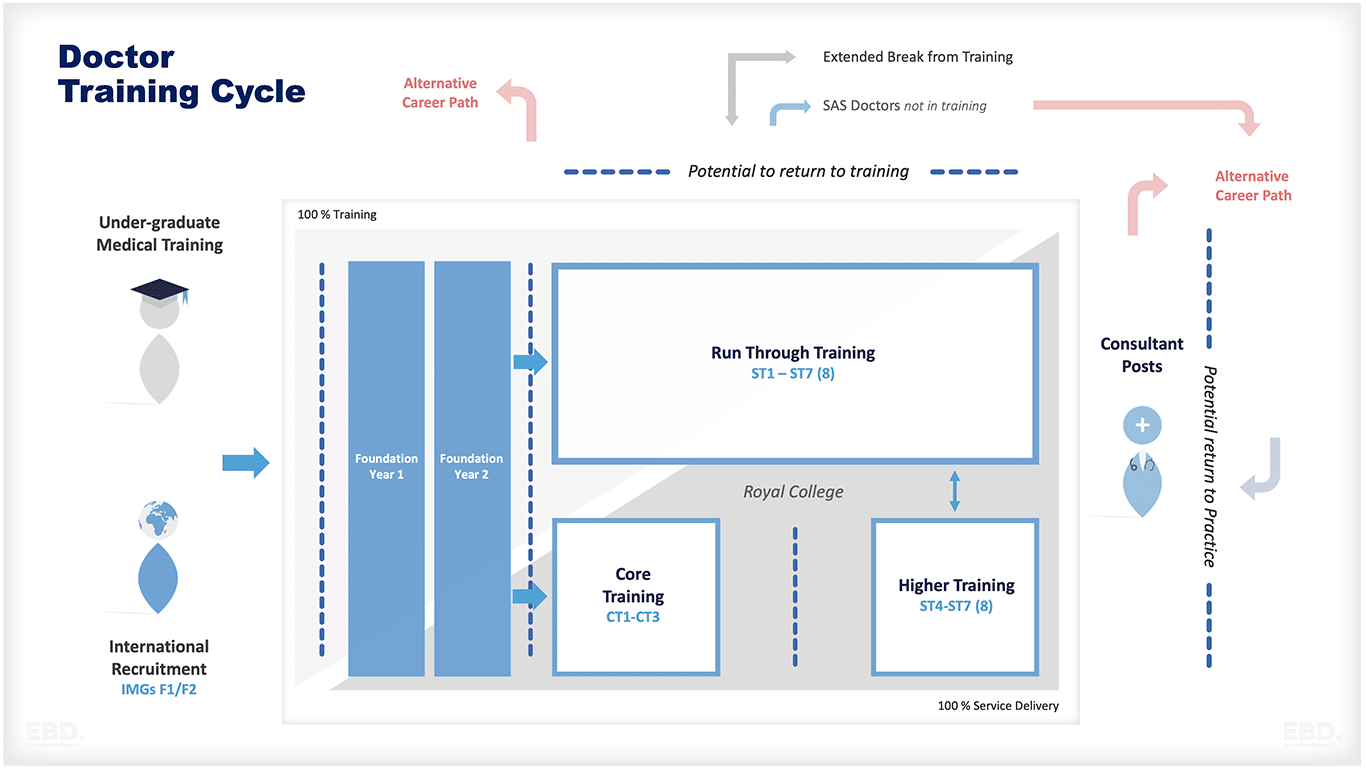

The figure below illustrates a typical training pathway for a doctor in the United Kingdom.

Undergraduate Medical Schools

This can last between four and seven years depending on the route taken. It is delivered by Higher Education Institutions hosting Medical Schools linked to Teaching Hospitals for Clinical Placements.

Here are some examples of medical schools + teaching hospitals from around the world:

UK

University of Oxford, Imperial College London, King’s College London, University College London, University of Cambridge, The University of Manchester.

Royal Free Hospital, St Thomas’ Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Guy’s and St Thomas’, NHS Foundation Trust and University College London Hospitals.

USA

Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine and Duke University School of Medicine.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Hospital and UCLA Medical Center.

Europe

RWTH Aachen University of Technology, Germany; Karolinska Institutet in Sweden; Uppsala University in Sweden; Université Paris-Descartes, France and Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, Germany.

Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam and Helsinki University Central Hospital.

Canada

University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine, McGill University Faculty of Medicine, McMaster University, Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine and the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine.

The Ottawa Hospital, Toronto General Hospital and Vancouver General Hospital.

India

Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College and Bangalore Medical College.

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Christian Medical College Vellore, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER) and Apollo Hospitals.

South America

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia.

Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología.

Asia

National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Peking University Health Science Center and The Medical School of Zhejiang University, Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health, National University of Singapore Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, The University of the Philippines College of Medicine.

National Taiwan University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Siriraj Hospital,The Philippines General Hospital, Singapore General Hospital and Chiang Mai University Faculty of Medicine.

Africa

University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences, Cairo University Medical School, Makerere Medical School and the Aga Khan University Medical College.

Groote Schuur Hospital in South Africa, Kenyatta National Referral & Teaching Hospitals in Kenya, Muhimbili National Hospital in Tanzania and the University of Ibadan Teaching Hospital in Nigeria.

Australia

Monash University Medical School, University of Melbourne Medical School, The University of Sydney Medical School and The University of Queensland Medical School.

Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, The Alfred Hospital and St Vincent’s Hospital Australia.

The global medical education landscape is continually evolving with new schools and hospitals being established each year to meet the ambitious goals set by their respective countries for healthcare services and standards. With this, there are also a variety of training opportunities available to doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals who wish to pursue further studies or specialise in specific areas.

Foundation training

This is a bridge between medical school and working as a trainee consultant. Full registration comes after FY1. The Foundation Year Programme is run nationally by the UK Foundation Programme Office (UKFPO) and delivered in hospital-based Foundation Schools. Trainees are paid to work full-time but are mainly involved in training activities on rotation. Posts are heavily subsidized by salary support funded nationally.

Some example of foundation schools:

UK

Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, University College London Hospitals (UCLH) NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

USA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Duke University Medical Center and Mayo Clinic

Europe

Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Hospices Civils de Lyon and Ziekenhuis Oost Limburg

India

All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER) and Christian Medical College Vellore

South America

Fundação Faculdade Federal de Ciências Médicas da Paraíba, Hospital Universitario San Ignacio and Instituto Nacional de Cancerología.

Asia

National Taiwan University Hospital, Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Medicine at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Chiang Mai University Faculty of Medicine, Institut Kesihatan Umum Malaysia (IKUM) and Singapore General Hospital.

Africa

Groote Schuur Hospital, Muhimbili National Hospital and Kenyatta National Referral & Teaching Hospitals.

Australia

The Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, St. Vincent’s Hospital and Westmead Hospital

Speciality Training

Progression through speciality training depends on the speciality. General Practice Specialty Training is 3 years post-foundation. Speciality training can be run-through for certain specialities OR can be uncoupled into Core Training followed by Higher Training. Trainees are paid full-time and are paid for by employers supported by subsidies funded nationally. Trainees rotate across posts that are allocated/approved by regional deaneries.

Royal colleges require candidates to pass membership exams to complete core training and speciality training – each college charges its own fees. Recruitment is coordinated nationally. Overall training is completed at the award of the Certificate of the Completion of Training by the General Medical Council (GMC).

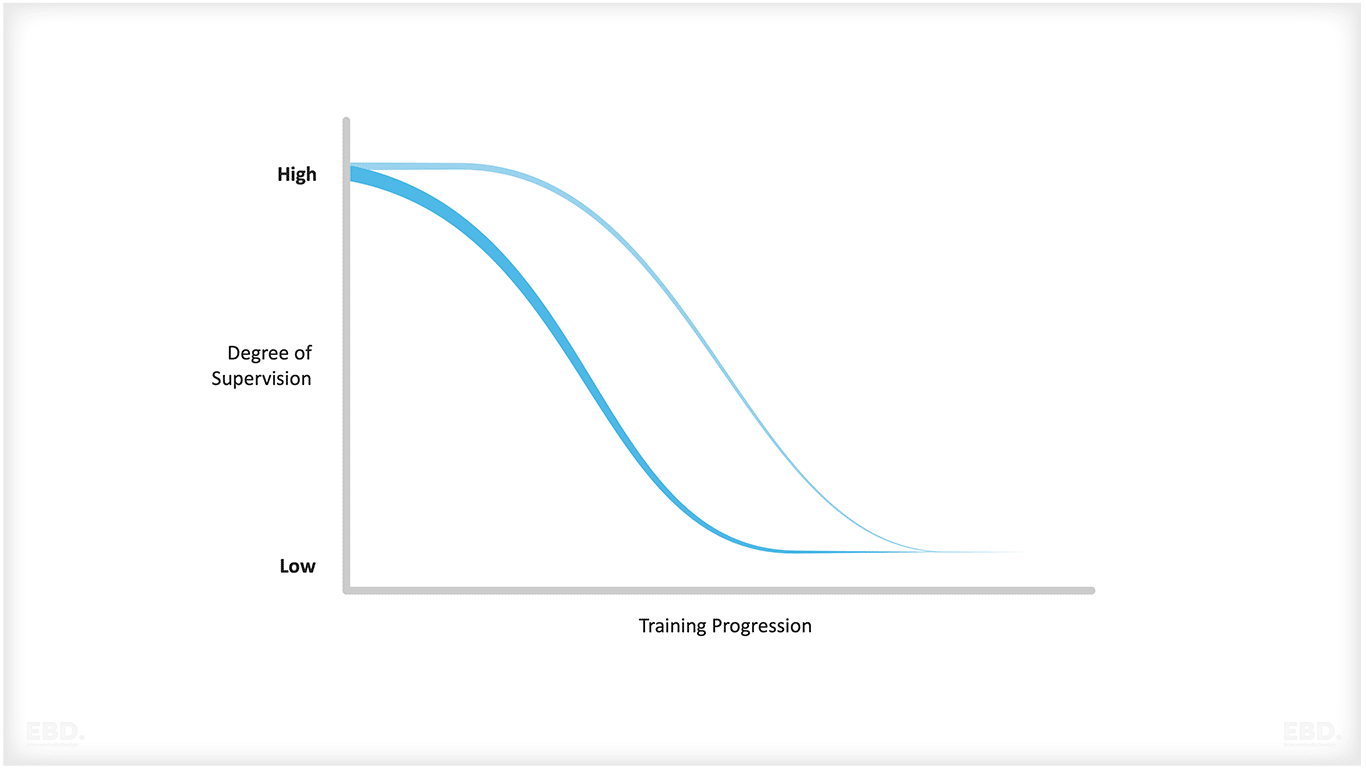

In the UK, speciality training and service delivery are closely intertwined. Overall, doctors in training in the NHS are thought to spend around 50% of their time delivering services unsupervised. That figure is lower at the start of their speciality training but much higher as they reach the point of completing their specialist training.

In Europe, rotation of posts is more common for specialty training and supervision varies across countries. Specialty qualifications are awarded by the European Board of Medical Assessors (EBMA), but the process and structure of speciality training may differ depending on the country.

In Asia, rotation and supervision is more common. Fees are variable depending on the country – Japan has a set fee for its speciality exams, while Singapore has variable fees according to speciality). Training may be funded directly by employers or individuals, but scholarships and grants are also available from the government and other sources.

In Africa, countries have developed competency-based training systems, while others are still using more traditional formats. Supervision is variable and fees vary between countries. Medical education has been heavily subsidised in some African nations, with grants available from the government or other sources.

In Australia and New Zealand, specialist medical qualifications are awarded by the Australian Medical Council (AMC) and the Medical Council of New Zealand (MCNZ). Supervision is usually provided by supervisors who have passed the relevant exams in their speciality. Candidates are expected to complete training in order to be eligible for registration with a professional medical body.

Registration

There are three types of GMC registration:

- Provisional – allows a newly qualified doctor to complete the general clinical training needed for full registration = this happens after graduation from medical school

- Full – allows doctors to work unsupervised in the NHS or private practice = this happens at the end of Foundation Year 1

- Specialist – this is required to work as a consultant = this happens at the end of specialist training.

Training Costs

Estimates from the PSSRU Unit Costs of Health & Social Care suggest that it costs around £250,000 (2022) to deliver a five-year medical degree per student. Once you include the two years of foundation training, this increases to £327,000. Reaching consultant level takes the overall costs up to £584,000.

These costs include tuition, living expenses and lost earnings, clinical placements and salaries of doctors in training. Most of the training is paid for by the government but some tuition fees – plus rent and living costs – are paid for by the student.

Medical Education Innovation

Opportunities for using innovative training programmes like Apprenticeships are also increasing. From 2023, in the UK, it will be possible for an individual to train to become a doctor through a new Medical Doctor Degree Apprenticeship.

Another interesting initiative is “credentials”. An example of this is the Credential in Breast Disease Management, for doctors who have completed their foundation years, to spend three years specialising as a Breast Clinician. Read more about this in our economic lens case study.

The NHS also has a programme for Technology Enhanced Learning. For medical professionals, the use of simulation, digital tools and advanced communication techniques have the potential to increase the opportunity to complement one-one supervision models with one-to-many supervision models which should reduce the overall supervision requirements for doctors’ training progresses.

What Is Continuing Professional Development?

Continuing professional development is how the healthcare workforce is increasingly expected to maintain their knowledge and skills. Healthcare is continuously innovating and improving and it is essential that healthcare professionals keep up-to-date with the latest evidence and standards of practice.

Continuous professional development involves attending conferences and seminars, completing online courses and learning from peers. It also includes writing for professional journals or carrying out research projects.

Often regulators require that health professionals participate in accredited programmes of continuous professional development to maintain their licence to practice. However, there is considerable variation across countries.

A European study (EAHC/2013) showed that across all EU Member states there was huge variation in whether continuous professional development was mandated, and for which professions, and there was also variation in whether participation in continuous professional development was linked to reviews of the professional licence to practice.

For example, in Austria, all of the main professional groups (pharmacists, doctors, midwives, nurses, and dentists) were required by law to participate in continuous professional development; however, this was not linked to license to practice. In Sweden, there was no mandate for continuous professional development for any of these professions.

What Is The Role Of Professional Regulators?

Each country has its own arrangements for regulating health professionals and setting requirements for registration and licenses to practise. Generally speaking, these regulators have a fundamental duty of care to protect patients and are responsible for:

- setting standards that need to be met by individuals in terms of competence, conduct, ethics etc.

- setting standards for education and training courses and clinical practice placements

- maintaining a public register of individuals who are licensed to practise

- address complaints and assess on-going fitness to practice.

Some professional regulators have evolved from professional associations that were originally established to represent and protect the professional interests of a group of specialist health professionals.

There is potentially a conflict of interest in this – between representing the interests of the profession and ensuring patient safety. This is why there needs to be a clear separation between professional associations and regulators, with the latter having overall responsibility for setting standards, regulating and monitoring professional practice.

A recent global survey of regulators (Besancon et al LINK) found that around half of the regulatory systems for health professionals were government regulators, with over a quarter being the responsibility of a professional body, and the remainder being a combination of both. This varied very little by professional group.

What Are The Key Challenges In Health Professional Education And Training?

There are a number of challenges to delivering effective health professional education and training. These include:

Keeping up with advances in technology

The rapid pace of innovation means that healthcare professionals need to stay at the cutting edge of digital and scientific developments and be able to use them effectively in their day-to-day practice. Continuous professional development can help with this, but oversight, consistency and relationship with fitness to practice tests are variable across professions and countries.

Quality Assurance

Ensuring that education training programmes meet the needs of healthcare and are delivered to a consistently high standard is complex. It depends on having effective quality assurance systems in place, with specific standards for each profession.

Cost

There can be significant costs associated with developing a curriculum and delivering training courses that meet the required standards. This may be particularly challenging in low-resource settings.

Achieving a balance between theory and practice

Healthcare education and training need to prepare graduates with both the theoretical knowledge base and practical skills needed for safe clinical practice. This is often difficult to achieve in short training programmes, particularly in settings where resources are limited.

Equity

Addressing any disparities in access to education and training for all health professionals, regardless of gender, ethnicity, or socio-economic background is a real challenge in all countries. It is especially important that the health professional workforce represent the patients and geographies they serve.

Outcomes Measurement

Assessing the outcome of education and training programmes on individuals and the impact this has on health outcomes is extremely hard to do but is important if effective, high-quality clinical practice is to be maintained across all disciplines.

To ensure that healthcare professionals are adequately trained and competent to practice safely, health professional regulators must ensure that providers of education and training courses and clinical practice placements meet minimum standards, so that graduates are competent and safe practitioners.

Regulators should also work with professional bodies to ensure that training programmes keep up with advances in technology, and strive to ensure equity in access to education and training for all health professionals. Lastly, they must measure outcomes from education and training programmes to assess their impact on health outcomes.

Workforce Planning

Often there is a disconnect between the numbers of university places, and the number of clinical training places required for progression through the training and development journey. Where governments take a lead role in workforce planning, these risks can be somewhat mitigated.

However, where education and training of the health workforce is uncoordinated there can be serious bottlenecks which result in wasted effort and talent, and/or shortages of particular groups of staff.

For a discussion of the challenges with workforce planning issues, please see this economic lens.

What Are The Key Costs Of Educating And Training A Health Professional?

Educating and training a healthcare professional can be very expensive. Costs can include providing infrastructure such as specialised equipment and laboratory space; salaries for staff to deliver the training; cost of curriculum development, examination and assessment fees. These costs can vary depending on the type of speciality and where in the world the education or training is taking place. In settings with limited resources, these costs can be prohibitively high.

In addition to these costs, there are also financial and opportunity costs that need to be considered. These include the cost of lost productivity while healthcare professionals are receiving education or training; the cost of recruiting and training replacement staff; and any lost revenue resulting from reduced patient throughput due to staff being away for study or training.

Overall, health professional education and training is one of the single biggest investments that a healthcare system makes. It is essential to ensure that all costs are taken into account when making decisions about investing in education and training programmes for health professionals.

Estimates from the PSSRU Unit Costs of Health & Social Care suggest that in the UK, it costs between £65000 and £66,000 to train a nurse, a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist, a speech and language therapist, a dietitian, a radiographer and a social worker. This compares with the costs of training a doctor to FY1 stage (registration) of around £312,000.

Useful References

World Health Organisation: Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030 (2016)

Okoroafor, S.C., Ahmat, A., Asamani, J.A. et al. An overview of health workforce education and accreditation in Africa: implications for scaling-up capacity and quality. Hum Resour Health 20, 37 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-022-00735-y

Besancon, LJR. Rockey, P. Zanten, M. “Regulation of Health Professions: Disparate Worldwide Approaches are a Challenge to Harmonization” (2012) World Medical Journal 58(4)( 127-136

EAHC/2013/Health/07 – Study concerning the review and mapping of continuous professional development and lifelong learning for health professionals in the EU

Contract no. 2013 62 02 FINAL REPORT.

PSSRU Unit Costs of Health & Social Care. University of Kent (UK). https://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/

Korpal, M., Kvas, Z., Abrahamowicz, M., et al “Cost Analysis of Health Professional Education: A Systematic Review” (2018) PLoS One 13(10): e0205218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone .0205218 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone .0205218 Accessed 27 March 2021.

Kaufman, D., Chen, L., Ivers, L., et al “Cost-effectiveness of human resources for health interventions” (2016) Human Resources for Health 14:64. https://hrh.bmj.com/content/14/1/64 Accessed 27 March 2021.